This is the second part of a two-part series, beginning with “From wagon roads to two-lane,” which can be read here. Part one explored motoring in Aspen from the first car in 1906 up to the completion of Highway 82 over Independence Pass in 1924.

After horse traffic gave way to cars, Aspen and the Roaring Fork Valley in the 1930s through the 1960s welcomed more automobile visitors. This was a time when autos and growth were compatible, and local family businesses still sold or produced what people needed. Road services appeared where adventurers wanted to drive, while affordable motels and slower food amenities popped up and wilderness still had plenty of room to spare.

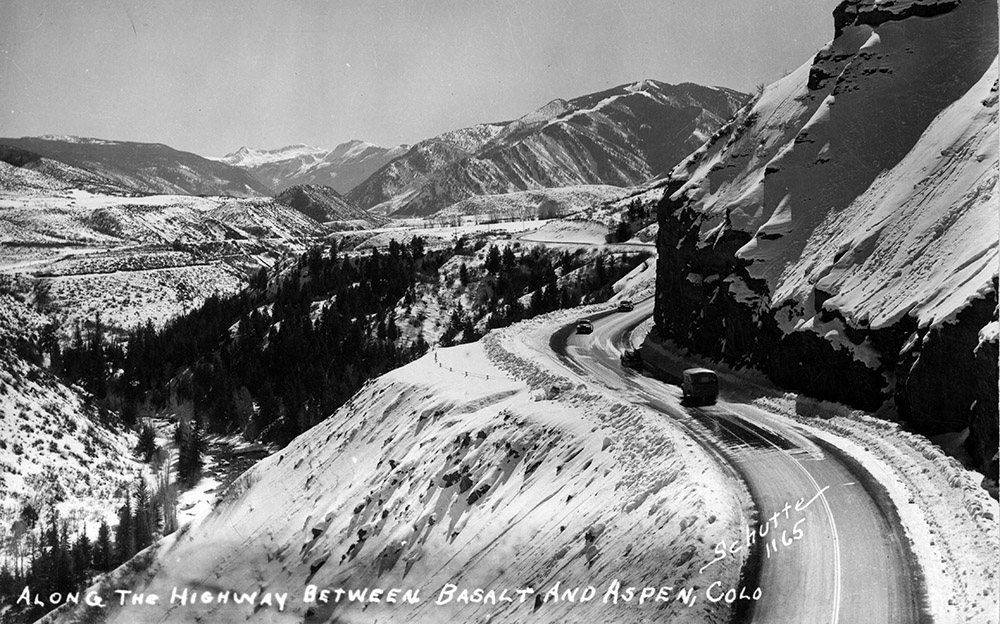

In 1941, Highway 82 was still open range. People complained about roving bands of horses on the road, belonging to “horse traders just trying to make an honest living,” said the Oct. 9, Aspen Times that year. As that traffic-comfortable era slow-boiled up to Aspen’s jampacked notoriety today, Highway 82 evolved from wagon trail to gravel road to oil-and-paved highway in 1938, fully paved in 1957, and to a completed four-lane upvalley from Basalt between 1992-2004. From 1962 through 1988, four-lane sections were stitched together between Glenwood and Basalt, according to a CDOT historical timeline.

In the early 1900s and into the 1920s, Colorado roads became better but the drivers didn’t. At first there were no driving rules and towns devised their own. Hand signals for turns varied and different colored traffic lights confused drivers. Police often had no cars and were on bikes, horseback, or motorcycles. By 1918 local police chiefs gave oral exams for Colorado drivers, according to the Dec. 10, 2019, Woodmen Edition magazine, while speed limits became more uniform starting in 1921.

In 1913 Colorado started licensing vehicles at $2.50 and officially requiring a state driver’s license in 1936 (Wyoming followed in 1947). Though 16 years of age became the standard, there were many much younger kids already driving, particularly farm kids, who were permitted locally off the main roads.

Snow drifts, frost heaves and ruts were constant complaints on Highway 82, but improved after paving. By 1960, the road had the highest percentage increase in traffic of any highway in the state, the Jan. 15 Times said. In 1967, the Independence Pass section was paved.

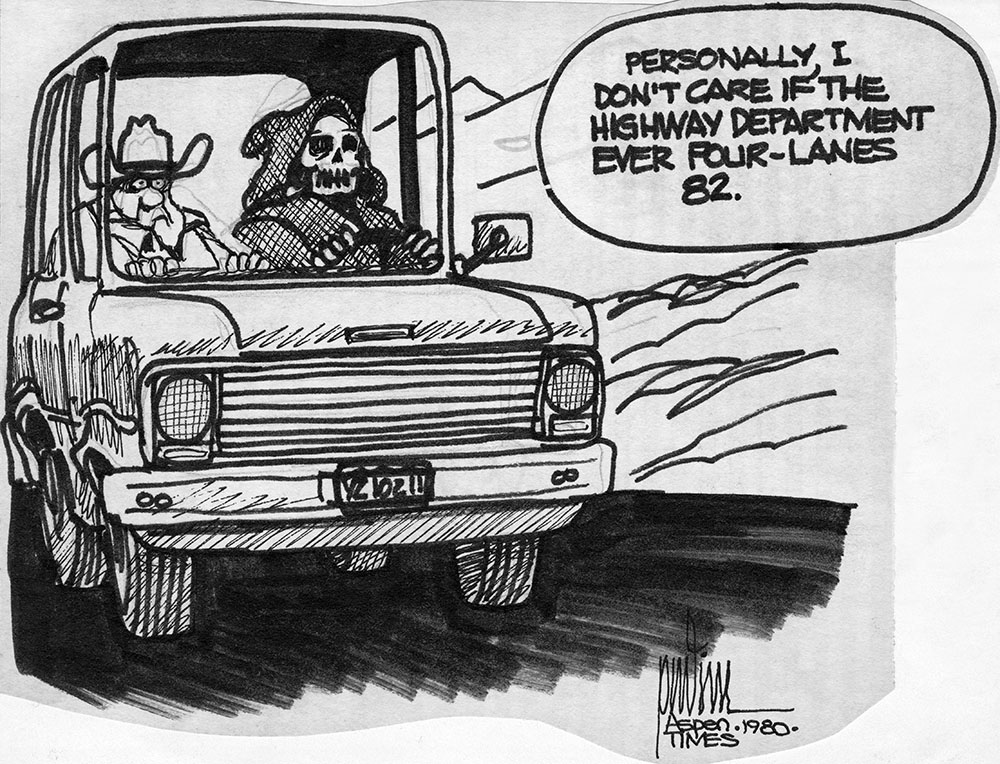

From then on traffic engineering attempted to keep up with maintenance and complaints. But as seasonal traffic and fatalities increased, the treacherous two-lane above Basalt with its old-west 65-mph speed limit, earned its 1960s-‘80s moniker, “Killer 82.” The Shale Bluffs section just east of the Snowmass Village turnoff with its shaded curves and falling rock, along a cliff above the Roaring Fork, was a particular area of fatalities.

Between 1992 and 2001, during a near decade of bottlenecks, blasting and road rage, state crews finished the four-lane to the Buttermilk ski area. This completed the earlier four-lane sections from Glenwood Springs, but not without controversy, because the project reined up just short of the money machine of modern Aspen.

Between 1975 and 2002, in a staggering series of 26 elections — according to an archival paper at the Aspen Historical Society — city and county voters voted and revoted on numerous proposals concerning the entrance of Aspen, involving paradoxical choices between two and four lanes, bus lanes, light trail, open-space rezoning, a straight shot and the S-curves, punctuated here and there by lawsuits.

Yet during the Quiet Years there was no S-curve, because the straight shot from the Castle Creek Bridge went straight down West Hallam — then a wider boulevard — or you might turn right toward Main. The upshot being that to this day most endangered Aspenites prefer the status quo as a kind of protective choke valve.

Drive here please

Cast a nostalgic view back to those Halcyon days of early two-lane roads, when visitors and agriculture supplemented a self-sufficient Aspen economy, and local stores sold pitchforks not $8,000 purses. Paved Highway 82 became an artery for commerce, as leisure auto traffic increased.

Yet automobiles caused problems. In 1939, the Aug. 10 Times reported that city council matched the state highways laws by passing tougher Aspen traffic ordinances, “covering drunken and wild driving, speeding and running stop signs.” Throughout Colorado ��most small towns and cities had adopted similar regulations,” the paper said.

As commerce and tourism comfortably increased, the Quiet Years in the Roaring Fork Valley sustained community. In the 1940s, auto rallies passed through town. In the 1950s, speedy, roadworthy foreign sports cars became popular nationally, leading to an annual race through downtown Aspen’s dirt streets with a dramatic straightaway down Main Street past the Hotel Jerome. A legendary, mischief-making Aspen doctor waved that checkered flag.

Bugsy Barnard

Serving as mayor of Aspen between 1966 and 1970, Stanford graduate Dr. Robert “Bugsy” Barnard came to Aspen in 1949 to practice. Characterized by the late Aspen writer Martie Sterling in a 1982 obituary as “a sodbuster, a gunslinger and a vigilante in an era of space technology,” Bugsy’s wild-west activism and love of the “sports car” led the Aspen Chamber of Commerce and Aspen Sports Car Club to design a car race in town.

Between 1951 and 1954, the fall event attracted more people and business than the Christmas ski season, and “volunteers were too few for the crowds … with Aspen’s motor courts, hotels and restaurants full” the Sept. 18, 1952 Times wrote.

In a time when second homes were few and short-term rental referred to skis, Aspen abided comfortably with cars. Then, eccentric local characters lived in town and Bugsy anecdotes were as plentiful as free-roaming dogs: He acquired his nickname after a failed scheme to bring slot machines to town; he and vigilantes chain sawed the mushrooming road signs on Highway 82; as mayor he replaced stop signs in the West End with tail-pipe scraping and coffee-spilling “Bugsy Dips” at intersections; paved much of town and coined the term “Killer 82” after attending to too many victims of highway accidents.

He and Freddie Fisher, Aspen’s colorful fix-anything man and opinionated wag, donned wigs, plaid skirts and saddle shoes to lead a “Mothers’ March” against the Aspen Ski Corporation, which had stopped giving Aspen children free ski passes in 1960, Sterling wrote. After losing his pass for protesting, Bugsy billed the company the exact price of his pass after attending to a ski accident on the hill.

In 1951, he managed to sell the sports car races to Mayor Robinson and the town. The first go-round held Sunday, Sept. 9, attracted a mix of sports cars and locals’ street cars. Aspen Mountain Ski Patrol director Lenny Woods patrolled the streets in a sound truck keeping people off the course. Hay bales were stacked on corners and residents with garden hoses watered the dirt-street course to keep dust down. Flagmen at corners signaled to spectators when cars were coming.

With the start and finish by the Hotel Jerome, a starter’s gun set off 11 competitors, the Sept. 13 Aspen Times reported, who ran to their cars from a Le Mans-style start, before starting their engines and roaring off. Jerry Johansen of Lakewood, Colo., in a blue Jaguar XK 120, took first with an average speed of 45 miles per hour on the twisting 1.7-mile course, blazing down the Main Street straightaway over 60. Vernon Meek of Grand Junction took second in an MG TD, with Ed Colt of Colorado Springs third in a supercharged MG TC.

Locals Otis Gaylord in his Willys Jeepster and Les Gaylord with his “vivacious wife Jean as copilot” in an MG made good showings. “To the surprise of many skeptics, Aspen’s first car race was safe and sane” without accidents or injuries, said the newspaper. Barnard, the event’s toast master, gave out gold-plated trophies sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Sports Car Club at the Aspen Meadows Four Seasons restaurant during the gala dinner.

Second year faster

After Motor Trend magazine featured the first race, showing Gaylord’s Jeepster careening around a downtown Aspen corner behind Johansen’s Jag, the second year turned out to be a much bigger affair with competitors from the greater west. Over 3,000 people attended, the Sept. 18, 1952, Aspen Times wrote. The weekend-long event kicked off with registration at the Red Onion Bar and Restaurant and ended with a banquet at the Golden Horn.

With an aim to make the Aspen Road Race one of the top attractions in the country, officials lengthened the course to 2.2 miles, with the turn off onto Main at Seventh Street, after roaring west up today’s Hopkins Avenue pedestrian/bike walkway. Though not documented exactly, after racing down Main, the circuit turned south on Galena Street before looping around the south side of town.

On Saturday of race weekend, a Jeep race up Aspen Mountain — not following the summer road — attracted numerous locals, in a time when old Jeeps were as numerous as Range Rovers are today. Mountain Manager Red Rowland, who built Aspen’s first ski lifts and who liked to say “I’d rather be a fire hydrant in Aspen than a millionaire anywhere else,” won first, with Wes Thorpe and Natalie Gignoux following.

That afternoon a “blind-folded race” took place in Wagner Park, where a blind-folded driver drove a flagged course dependent on a backseat driver yelling the directions. Race winners were Gignoux with backseater Arthur Madigan, with Dr. Barnard and Bob Wright in second.

On Sunday, the 4H Club sold hotdogs and soda pop (proceeds donated to the hospital), to the packed spectator stands along Main Street. Top competitors in the 25-lap main event with 22 entrants—running in five categories depending on engine size and modifications— “hit one hundred miles an hour on the straight-away” down Main Street, the Times wrote.

Preceding the main event, a downtown concours d’elegance display of polished exotic sports cars and race cars in attendance allowed spectators to view the merchandise close up. Then a five-lap women’s race followed, “enlivened by one Penny Du Bois, a tall hard-faced female driving a German Porsche,” read the Sept. 18 Times. The Porsche disqualified and the winners were Ruthie Brown of Carbondale, Georgia Jones of Aspen second, and Dorian Phipps of Denver third.

Though a no-show, rumors that two “$16,000 Ferraris” from the national dealer would race circulated beforehand. Instead, in the men’s race, fans watched Kurt Kircher of Denver in his Chrysler V-8 Allard, a low-slung modified race car, run away from the field. Aspen’s Whipple Jones, who would go on to start Aspen Highlands in 1958, took third in his modified Jaguar.

After the annual event grew, enhanced new safety requirements included shatterproof goggles, taped glass, helmets, seat belts, and auto inspections. Some 30 deputized Aspen men acted as race marshalls to patrol the course and prohibit anyone from crossing the track, while more hay bales and chicanery modified speeds.

The 1953 and 1954 downtown events that followed, as reported by the Times in September of those years, attracted national attention. The wild-west Aspen Car Race, as it became known, screeched to a stop just before the 1955 race, when Gov. Ed Johnson stopped such use of public roads, but ran one more time in 1957 in a throttled-back version after new Gov. Steve McNichols gave the OK.

“Saddle Sore” Aspen Times columnist Tony Vagneur recalled the races as taking over Aspen, and that as a kid he ran about town “at a dead run” while pushing an old Victorian baby buggy given to him by Judge Shaw’s wife, pretending he was a race car.

Highlands race course

As the freewheeling 1950s gave way to the infamous 1960s and liability began to fence in more things, Aspen was unable to get insurance to resurrect downtown car races. To get around that, Whip Jones set up a temporary half-mile course out at Highlands in September 1961, using the big parking lot and the lower mountain access road, with viewing from the hillside.

The Sep. 15 Times previewed the Highlands race weekend, announcing a display of exotic cars at the Aspen Meadows, along with over 50 MGs from the Denver MG club finishing their rally tour of Colorado in Aspen. And Aspen Imported Motors at Galena and Hopkins — about where Dior and Gucci are today, and around the corner from Stan’s auto body shop on the site of today’s Baldwin Gallery — advertised a used Porsche and Austin Healey, both ready to race.

Fifteen races ran at Highlands that weekend with C. S. Trosper of Oklahoma City taking first in the premier race in his Porsche Super 90, Robert Hagestad of Denver second in a Porsche 1600, and Barnard third in his 120 Jaguar, the Sept. 22 Times reported. Among other races were a women’s race won by Aspen’s Mrs. Peter Green in a Porsche, a local sedan race, a Corvair and a VW race, with one VW rollover and no injuries. Young rancher Rick Deane raced a “hotrod special.”

Woody Creek Raceway

In 1962, with real estate around Aspen as available as disposable income today, Dr. Barnard and his partner Dr. J. Sterling Baxter, by then both racers about the Colorado circuit, solicited donations from businesses and residents to buy 45 acres on the flats in Woody Creek from the Vagneur Ranch to build a permanent raceway.

Supported as a business angle to attract more people to Aspen in early summer and fall, the track had been a dream of local sports buffs, the Dec. 14, 1962, Times reported. The Western Sports Car Club of America, including Grand Junction, Glenwood and the Aspen chapters, backed the project. The first race was scheduled for July 4, 1963. Barnard oversaw the track committee until he left town after losing a 1975 mayoral comeback bid against the incumbent, anti-growth downtown bartender Stacy Standley.

In the 1970s, the track was unlocked and without fencing. Anyone could take their car or motorcycle around the track to see what she’d do. Bets were settled between motorcyclists in town with face-offs on the straightaway. Here and there locals’ stock car races ran out at the track in between WSCCA races.

Among entrants were the fabled Aspen State Teachers’ College with driver Slats Cabbage, and the infamous “The Pub” bar — headquartered in the Wheeler Opera House basement — sponsoring the “Intimidator.” For a few bucks admission, race fans could park on the hillside, tour the pits freely, and squander a scorching July afternoon drinking beers from their own coolers.

In the spirit of the era, the first overhanging stoplight in Aspen, a blinking caution light west of Aspen Street and Main, was shotgunned one early morning in the mid-1970s. The culprit bragged about it at The Pub.

Demo derby

But a highlight of old free-form Aspen happened circa 1972 when a spontaneous demolition derby took place at the Woody Creek track before a stock car race. Many Aspenites then had “town cars,” beaters they were afraid to drive downvalley. Roland “Gloves” Barden, of the Smuggler Trailer Park, drove a barely maintained 1948 Packard convertible only in town.

As eyewitness recollections go, with folks of all stripes still living about town with jalopies in their yards, word spread the day before and some half-dozen locals rumbled their entries to the track.

Always game, Barnard let the demo derby roll. Retired motorcycle racer Mike Vanness fired a shotgun in the air for the start, and some half dozen clunkers— what would be vintage cars today — started ramming one another around the infield, mostly backing into each other to save their radiators, while raucous spectators cheered. The unwritten rule was ram anywhere but the driver’s panel.

According to raconteur Jim Wingers, the one-time gearhead “CEO” of “Queen Street Limited” diversified enterprises, run out of the ramshackle “Green Acres” neighborhood across the street from today’s Herron Park, the finale came down to two Detroit steeds, with a Volvo first out. Wingers, aka “Bat,” whose memory banks are linked by the make, model and year of cars involved in any story, recounts Romeo Pelletier in a “‘57 Plymouth wagon,” “Montana John” Tange in a “‘64 Chevy four-door,” Terry Cubbins in a “‘59 Olds,” and Wingers in a “‘58 Caddie Deville convertible.”

As punctured tires hissed flat and radiators steamed, local rivalries played out in a war of attrition, leaving disabled clunkers strewn about. In the finale, Wingers and Pelletier bashed it out to a standstill that appeared to be a dead tie. But somehow Pelletier managed to restart his engine and roll two feet to take the win. Barnard pushed the wrecks off the track with an old bulldozer before the main stock car event rolled.

Weeks later a second demo derby offered a rematch. Wingers outlasted the field with an assistant in the backseat of his “‘55 Pontiac four-door,” who poured extra water from eight gallon-jugs into a hose that went through a hole in the hood to replenish the radiator. As demo derby fans know, the first to be eliminated are those with a blown radiator, quickly leading to a seized-up engine.

Auto and motorcycle races continued into the 1980s and 1990s. After idling for a few years, the track became privatized and fences and gates went up. Today the track, called the Aspen Motor Sports Park, is secured up tight with a resident watchman, operating as a private club for members and special events.

Traffic daze

From the mid-1980s on as traffic multiplied on Highway 82, long-term locals started moving downvalley or beyond — many because of too much change, loss of familiar community, or to cash in. At the same time, locally owned what-makes-a-town businesses began diminishing, displaced by luxury stores, galleries and real estate operations that have increased exponentially to the present.

The result being that remaining Aspen residents and businesses had trouble finding skilled tradesmen, employees or services locally. Upvalley traffic of workers, contractors and commuters filled that void, while Aspenites began driving downvalley for most necessities. Thus, by catering to an Aspen that could no longer sustain itself, like a pampered queen bee, the right to access town to make an upvalley living for a better life downvalley became a rallying cry for the four-lane in and out of the honeypot.

This upvalley right-to-access came with the pricing out of Aspen as a self-sustaining business community, deflated by rocketing land values pushed by outside speculators. Yet Aspenites fought back through many self-preservation ballot proposals and anti-development growth initiatives, voting no in 2002 to the last critical highway link that would have allowed the four-lane to ramrod through the Marolt Open Space straight into town on Main.

Today, competitive and expensive downtown parking and steroidal backup complement gridlock in and out of town during peak times. And in summer and fall at the other side of town, the Indy Pass entrance brings bumper-to-bumper visitors, necessitating for the first time a stoplight in the narrows section of the pass last summer.

Short an economic downturn, many still believe that finally a four-lane straight shot into town would help the problem, while others believe a four-lane into a mountain-valley that remains a cul-de-sac for its busiest six months would be like filling a barrel with a fire hose.

Our romance with cars was fun, affordable and brief. We asked for more cars, and we got them.

This story ran in the Aspen Daily News on May 15.