As more recreationists are drawn to Colorado public lands, wildlife officials have noted changing patterns in elk herds’ health, population numbers and habitat. Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials are considering several changes aimed at managing both the elk population and complaints of hunter overcrowding.

In presentations to Garfield and Eagle county commissioners, wildlife biologist Julie Mao said elk herds in northwestern Colorado face a host of challenges, including drought and climate change, energy development, residential development and recreation. Although elk population numbers in northwest Colorado, including Pitkin, Eagle and Garfield counties, currently meet objectives set by the state, those numbers are probably not sustainable, Mao said.

The ratio of calves to cow elk — a measure of herd resiliency — has steadily declined over the past four decades. This means that as older elk die, fewer young are there to replace them.

Meanwhile, the state’s hunters have expressed concerns that they see more humans than animals during hunting seasons, especially as large numbers of out-of-state visitors acquire licenses over the counter.

“A big part of what we try to do is try to balance the biological capabilities of the herds with public demands for wildlife recreation,” said Joey Livingston, statewide public information officer for CPW.

This winter, CPW commissioners will consider limiting those over-the-counter licenses, while local officials work to update herd-management plans that set population goals for the elk herds.

At a meeting in August, officials proposed changes to the big-game hunting season structure that could mean fewer licenses for hunting bull elk in areas that have unlimited over-the-counter licenses, including much of northwest Colorado.

In the current system, licenses for many rifle elk-hunting seasons and areas are available through a lottery-style draw process, and in some cases, there are highly limited hunting opportunities. (Hunters accrue points over years in this process, and next year, 75% of licenses in the draw will be reserved for Colorado residents.)

But both residents and visitors can obtain unlimited over-the-counter licenses to hunt large bull elk in the second and third rifle seasons in about 90 hunting units, including many in the Roaring Fork Valley and northwest Colorado.

That could soon change. State officials are working on updates to the season structure that could include limiting over-the-counter licenses in an attempt to reduce crowds.

Hunters and outfitters told the CPW commission in August that there are too many hunters and not enough animals on the landscape.

Tyler Emrick, who owns CJ Outfitters in Craig, told the commission that he hasn’t accepted hunters with over-the-counter licenses for the past three years because of overcrowding and limited elk numbers.

“Who’s going to hunt elk if all they are going to see is sagebrush? Or (hunt) deer, if all they’re going to see is sagebrush and other hunters?,” Emrick said. “We should really focus on getting our populations back.”

Surveys and polls at in-person meetings show support for reducing the number of over-the-counter licenses available. Fifty-seven percent of respondents supported limiting licenses for elk, and 68% wanted those limitations to be implemented through a draw.

CPW staff presented the feedback from months of public meetings, sportsperson caucuses and surveys at the August commission meeting and in a summary report.

“Many resident hunters feel that the opportunity to purchase an OTC (over-the-counter) elk rifle or archery license should only be made available to residents,” wrote CPW staff members in a summary report. “In the opinion of many resident hunters, OTC licenses should be limited for nonresidents statewide, whom they feel should instead apply through the draw process. Meanwhile, most nonresident hunters prefer the status quo, which gives nonresident hunters the same OTC opportunity as residents.”

About 2,200 people responded to surveys and 300 attended in-person meetings. State wildlife staff will develop recommendations for the season structure, including the potential to limit over-the-counter licenses, and expect to present to the commission in May.

Proposed changes to season structure unlikely to increase elk population

Limiting over-the-counter licenses would reduce crowding, but it wouldn’t address dwindling elk populations.

Those licenses primarily allow hunters to kill large bull elk, and the available seasons are intended to be after those animals have had the opportunity to breed. Hunting bulls doesn’t have a large effect on population numbers.

“As long as you have some bulls, they’ll be around to mate with the cows,” Mao said. “It’s really the cows that affect population size.”

That is why cow elk-hunting opportunities have been extremely limited in certain herds on the Western Slope. Although most herds have populations that fall within CPW’s objective range, the ratio of calves to cows continues to drop. Biologists use this as a measure of how resilient the herd is to stressors such as drought, development and disease.

In the 1980s, when CPW first began conducting helicopter surveys to count animals, there were roughly 60 calves per 100 cows; now the number of calves has dipped into the 30s per 100 cows for elk herds in the Roaring Fork Valley.

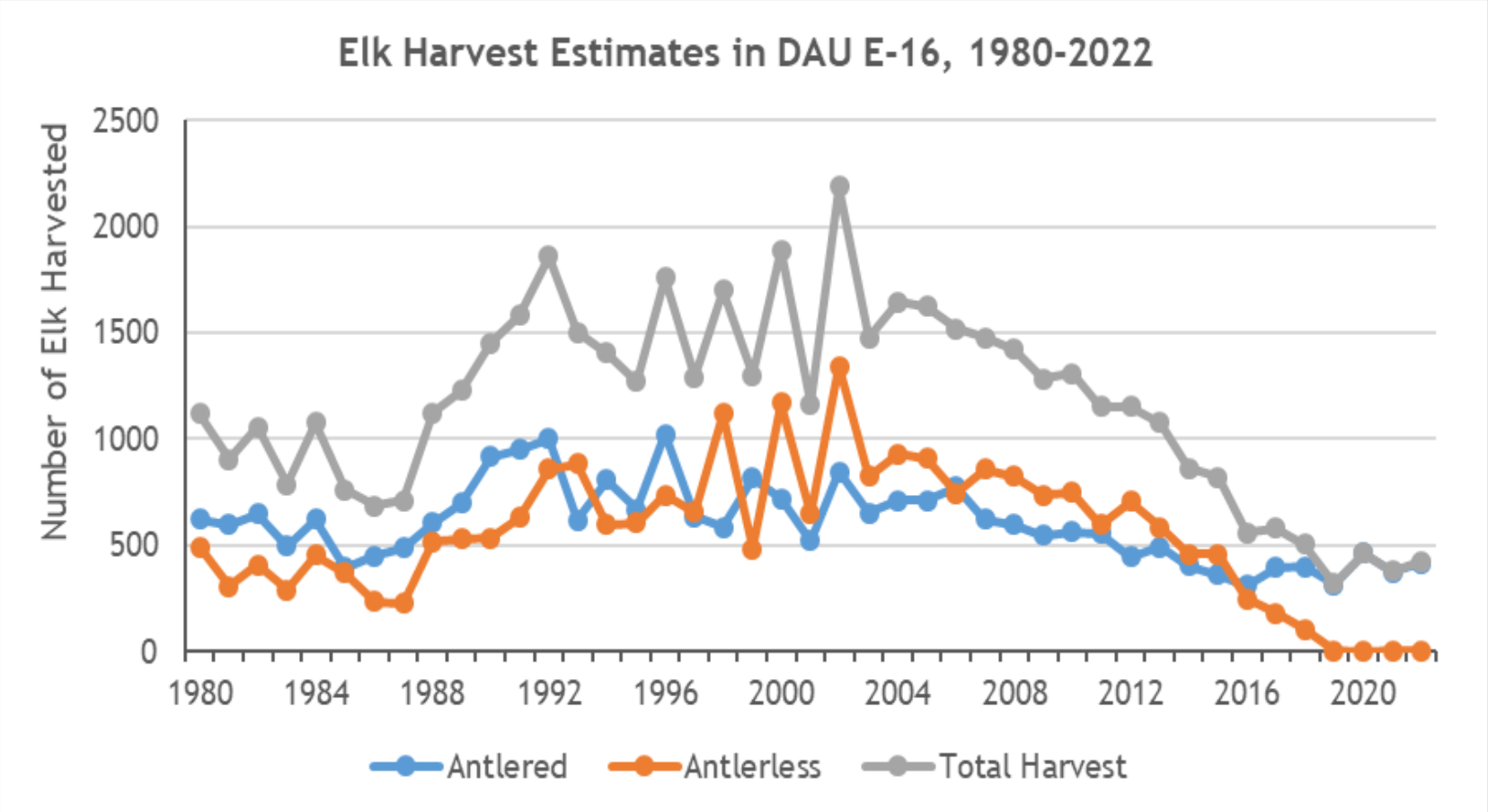

As fewer young calves are born into herds, CPW officials have limited the number of cow elk-hunting licenses to preserve population numbers. The Fryingpan elk herd, which lives east of the Continental Divide and roughly between Interstate 70 and Highway 82, dropped below the goal of 5,500-8,500 elk in 2017. CPW drastically reduced licenses for hunting cow elk.

Although hunters in the early 2010s used to harvest between 400 and 700 cow elk in the hunting zones that make up the Fryingpan herd’s terrain, that number has dropped into the single digits for the past four years.

The elk population in the Fryingpan area has since rebounded as a result of these hunting limitations; in 2022, it was estimated at 8,511 animals, which tops the CPW objective. But Mao told Garfield County commissioners that this number could be deceiving.

“The population increase is somewhat artificial because it’s not something that we can sustain in the long term,” Mao said. “Those cows are going to get old and eventually die, and we also want to be able to offer cow-hunting opportunities. It’s not our goal to eliminate cow harvest perpetually in that unit.”

CPW aims to keep elk numbers steady even as threats continue to grow

In presentations to Eagle County and Garfield County commissioners, Mao and her colleagues at CPW said that current population objectives for herds in Pitkin, Eagle and Garfield counties are reasonable and are likely to hold steady in updated plans.

Even so, Mao points to a series of compounding issues that make long-term survival of the herds more challenging.

Energy development, including oil and gas developments and solar developments, causes habitat fragmentation and loss. In cases where fencing is required, “for elk and other wildlife larger than a mouse or rabbit, those are a complete loss of habitat,” Mao said.

Housing and other urban development and recreation continue to push people farther into what was once prime habitat for elk and other large mammals.

“There’s people on the landscape just all over the place,” Mao said. “Public lands that used to be good summer range and used to offer animals areas of solitude, now there’s a lot of trails everywhere. Even in the backcountry wilderness, where in the past it might have been surprising to find people way back there, now it’s almost expected.”

As the elk population in the Fryingpan area has rebounded, Mao said there is a noticeable change in where the herd spends time.

“We’re starting to get more elk that are potentially even not migrating anymore and they’re hanging out on private lands because now compared to public lands in the summer, private lands are less busy,” Mao said.

As the distribution of animals shifts, hunters complain that they aren’t seeing the numbers of animals they’d like, even if population numbers remain steady. Meanwhile, property owners may see increased game damage on their private lands.

Public-land managers, including the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and local open space and trails agencies, often use seasonal closures to mitigate the proliferation of recreation. But Mao said this compromise, which is intended to protect elk during their most sensitive times, winter and calving, relies on help from the public.

“It’s really up to people to be responsible and follow the rules,” Mao said. “We can’t ask for all the habitat back, but at least of what habitat remains, it’d be nice if people could help out and adhere to seasonal closures, keep your dog on leash.”

Mao and CPW area wildlife manager Matt Yamashita are scheduled to present updates to local herd management plans to Pitkin County’s board of commissioners on Dec. 12.