One August day in 1930, John H. Cowden, president of the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company of Ordway, Colorado, and his engineer O.R. Smith stood atop Independence Pass looking for water sources. Gazing west, they marveled at the Roaring Fork Valley’s abundant supply. A biblical idea struck: Bring what they viewed as “unused water” through the Continental Divide to the east side.

Four years later, the Aug. 2, 1934, edition of The Aspen Times reported that a thousand people showed up on a Sunday in late July to watch Tex Romig and William “Dynamite Bill” Rainger of Leadville officiate a rock-drilling contest between the highly competitive drillers of the East Portal and West Portal of the government-financed Independence Pass Transmountain Diversion Project. The plan was to divert the “excess waters” of the upper Roaring Fork basin through a 3.8-mile tunnel to the parched dirt farmers of Crowley County on Colorado’s southeast prairies.

Held on the “rugged slopes of the Eastern Portal of the ‘Big Bore’” on North Fork Lake Creek, the “machine gun-like staccato of the drilling machines” punctuated the day-long fete. Project contractor and party sponsor Platt Rogers Inc. of Pueblo supplied food and ample refreshments.

Members of the competing teams were already working long days to complete the 8-foot-wide tunnel begun in September 1933. The Nov. 22, 1934, edition of the Times reported a particularly tough section of solid rock where workers pushed 8 feet at a time, after each 200-pound dynamite charge. The explosive sets required 30 6-foot bore holes for placement of the volatile sticks.

Deep underground, with deafening noise and little ventilation, the tunnel project ignited camaraderie to meet in the middle — an engineering feat in itself. Once the upper waters of the Roaring Fork’s spring runoff were corralled, the tunnel would stream it east to Lake Creek and Twin Lakes, then augment the Arkansas River to feed the Colorado Canal headgate in Boone and ultimately irrigate crops of sugar beets, cantaloupe, alfalfa, wheat and corn 200 miles downstream in Crowley.

Many tough hard-rock miners were happy for steady work during the ongoing Great Depression era that had just peaked at 25% unemployment, yet the drillers still had enough gumption to go all out for a contest on their day off.

East Portal wins

Twenty teams of two people each raced time to drill a 6-foot bore hole in solid rock, the Times recounted. With the stopwatch running, the cycle included setting up the drilling machine, changing drills three times (2-, 4- and 6-foot lengths), dismantling the machine and returning it to the starting point with all hoses coiled.

The first-place award of $100 ($2,000 in today’s currency) went to East Portal’s Cook and Box, who finished in 7 minutes, 3 seconds. Second place ($50) went to West Portal’s Musick and Fohn, who finished in 7:15, and third ($25) went to West Portal’s Mckee and Mathis, who finished in 7:17 for $25. Another East Portal team took fourth, winning a coupon for $10 worth of gasoline, which cost 19 cents a gallon then. The longest time taken was 10:42, while some took reruns on technicalities.

The East Portal celebration also featured a retro demonstration of accuracy and endurance. Prior to the then-modern pneumatic drills — dubbed “widow makers” when first developed in the 1870s — small-budget miners used the “single-jack” or “double-jack” technique to hand-bore dynamite holes. “Jacks” were the miners, and the moniker was coined because everyone had a “cousin Jack” looking for a mining job.

Single-jacking involved an individual holding and turning the steel bit with one hand while hitting it with an eight-pound sledge hammer in the other. Ambidexterity was helpful. In double-jacking, one or two drillers hit the steel with an 8-pound sledge hammers while a trustful holder turned the steel slightly between raining blows. Up until 1900, big-purse jacking contests were popular.

Back to work

On the Monday after the rock-drilling competition, about 175 workers from Pitkin and Lake counties went back to work on Tunnel No. 1, piercing the Continental Divide 2,200 feet underground through Independence Mountain, with the expectation of delivering 25,000 acre-feet of water to the eastern slope annually, the Aug. 9, 1934, edition of the Times projected.

One acre-foot of water is enough water to cover an acre of land a foot deep. This equates to 326,000 gallons, about what two large families might use in a year. Ruedi Reservoir, for example, holds about 100,000 acre feet.

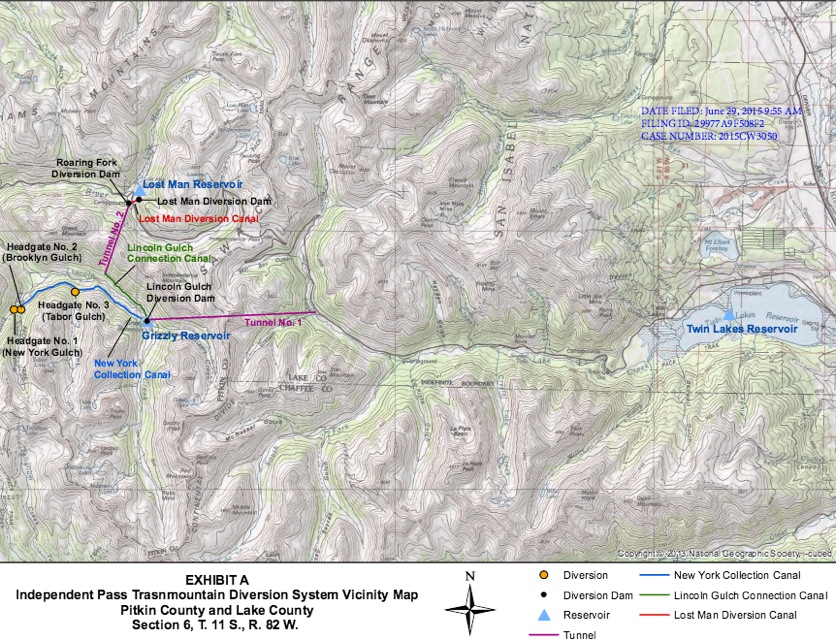

The first part of the project provided a welcome boost of employment to Aspen’s tight-knit community of about 700 people, many subsisting on potatoes, fish, jackrabbit and venison. The first phase included the construction of Lincoln Gulch Dam Reservoir, now called Grizzly Reservoir, and a canal that gathers water from Tabor Creek, the creek in Brooklyn Gulch and New York Creek.

The second phase, scheduled to begin by November 1935, included a shorter, narrower second 1.9-mile tunnel that would nearly double the amount of water going east from the Roaring Fork watershed.

By boring under Green Mountain from the upper Roaring Fork River — just above today’s Lost Man Campground — to the Lincoln Creek valley, the second tunnel — Tunnel No. 2 — would send water to Grizzly Reservoir and then into Tunnel No. 1, which starts at the edge of the reservoir.

Tunnel No. 2 also moved water from Lost Man Creek, via a dam that forms Lost Man Reservoir and a canal that moves the water from the reservoir to the main stem of the Roaring Fork, where there is a riverwide dam that sends water into the mouth of Tunnel No. 2.

The total combined job, which included the two cement-lined tunnels, feed canals, two reservoirs and three dams, wrapped up in December 1936 — without gold or silver strikes — providing three and a quarter years of steady work and about 300 jobs.

But all this came not without deaths, injuries and incidents.

Tunnel perils

As work neared completion, a Dec. 3, 1936, Times story recounted some tragic details from chief engineer O.R. Smith. Earlier, on June 25, a Times report recounted a shooting fatality involving rowdy tunnel workers.

Yet, Tunnel No. 2 contractor S.S. Magoffin of Oregon, who bid lower than contractor Rogers of Tunnel No. 1, set a safety record according to Smith, by finishing with only five hospitalization injuries among workers and no fatalities.

As for Tunnel No. 1, along with assorted hospitalization injuries, three men were killed instantly in separate incidents. “One was electrocuted, another received a crushed skull when a reducer cap on an airline blew off and struck him, and another was caught by a mucking machine and crushed to death,” the Times reported.

Two of the fatalities occurred by carelessness, Smith related. The electrocuted employee “was known to be frisky with live wires,” and the airline cap had only been “screwed on by three threads.” The mucking machine fatality “was termed unavoidable because the drag-line cable jumped the drum and caught the operator.”

Prior to the shooting death, five tunnel employees on a drinking spree after work, led by “Frank Hallet of Tabernash,” ended up “starting a rough house” in Glenwood Springs. They decided to call on friends they thought were still living in a cottage there. Unbeknown to the five workers, however, “respectable people” were now renting that cottage.

Hallet and his posse barged in “demanding things for their own gratification,” whereupon one of the new occupants, William Loney, ordered them out of the cabin. Loney was then beaten, but he managed to grab a .25 caliber pistol and shot Hallet point blank, causing the instigator’s partners to scatter.

Hallet, survived by a wife and two children, died at the Glenwood hospital from a wound in the left side of his chest. Charges against the surviving rowdies remained undetermined, while those against Loney were dismissed, the Times reported.

Rowland’s rollover

In another misfortune, Harold “Red” Rowland, employed as a tunnel worker and who would later go on to be Aspen Mountain’s first mountain manager, lost a wheel from his 1934 Chevrolet while coming down Independence Pass after work with three other tunnel workers as passengers, the April 4, 1935, edition of the Times reported.

During that low snow year of 1934-35 (127 inches, according to City of Aspen records), Rowland apparently pulled out “to pass a team and wagon on a curve” and the Chevy’s left-front wheel collapsed.

The car rolled 200 feet down an escarpment “seven miles from town,” ejecting Rowland, Earnest Moulton and J.B. Phelps, while Francis O’Neal remained in the vehicle as it came to rest. O’Neal sustained slight injuries, and the others walked away unhurt. The car was totaled.

A seven-mile reckoning suggests the sharp curve and embankment just below today’s Weller Lake parking. At least into the 1980s, a rusted, indistinguishable wrecked car rested among the boulders below near the creek.

Undeterred, Rowland later became a supervisor for the tunnel project and drove state dignitaries up to the “Hole Thru” party later held at the Lincoln Creek tunnel entrance at the soon-to-be-completed Grizzly Reservoir. With his promotion, Rowland later purchased a new Oldsmobile, a Times column noted on July 8, 1937.

Red’s brother Leo “Pope” Rowland was said to make moonshine and sell it to the tunnel workers. A renowned contrarian about town, in the 1970s and 1980s he refused to sell to developers his junk-strewn downtown lot kitty-corner to today’s art museum. During that time, a portion of Aspen’s bygone marrow, “The Christmas tree lot,” held forth on the lot with Pope’s blessing. Some suspected his still was in the now-shuttered Main Street Café building, formerly Little Cliff’s Bakery that Pope owned before Bill Little.

Government money

The first massive U.S. government bailout program, called the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, financed the Independence Pass project in 1933.

Enacted in January 1932 by President Herbert Hoover and expanded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after the 1932 elections, the RFC initially propped up banks with $2 billion ($39 billion today) to broker business loans, many of which funded back-to-work projects such as the Independence Pass diversion plan.

Overseen by a presidential appointee who doled out preferences, the RFC aimed to jumpstart the crippling economic contraction between 1929 and 1933, brought about by the 1929 stock market crash, bank failures and a rush to exchange gold-backed dollars for gold in the headwind of counterintuitive, Fed-imposed rising interest rates.

Many such government programs during the 1930s were credited with putting the U.S. economy back on its feet in time for World War II to add the nitro acceleration. Curiously contemporary in situation, the transition from a rigid laissez-faire administration to interventionist during an economic crisis made the 1932 national elections a critical turning point and a future showcase for Keynesian economics.

Rain-barrel rebellion

Centered on ranching, barter and belt-tightening, Aspen’s economy in the 1930s was already threadbare after the 1893 silver crash — although some mines still employed small crews. And for the most part, the Roaring Fork River still ran mostly full with its native flow, often flooding riparian areas naturally.

Cited in 1930s newspapers as one of Colorado’s mountainous “rain barrel counties,” Pitkin County harbored the water-rich Roaring Fork basin. Historically, the Fork shared its bounty of snowmelt downstream, running into the Colorado River in Glenwood Springs and far beyond the Utah border and on to the Grand Canyon.

But the vast plains across the Continental Divide to the east, plagued by drought and winds that scattered topsoil from overplowed prairies during the worsening Dust Bowl, and the need for paychecks and farm-grown food stood in stark contrast. Everywhere, jobs remained a premium.

Still, once the upper Roaring Fork was diverted to the rescue, many in western Colorado, and Aspen, felt an underlying sentiment that the legal hijacking of “their water” constituted an expropriation of nature.

But to Colorado water law, the Continental Divide is just a geographical ridgeline that has no legal bearing as an obstacle, obstruction or violation of the natural order when filing water appropriations within the state.

A fundamental tenet of water law is that the right to use water is based on an application of a quantity of water to a beneficial use, such as irrigation.

And appropriation of water followed the “first in time, first in right” principle established in the early mining days when conflicting claims were sorted out in court. Rough-and-tumble western mining camps devised these first-on-scene rules as a mutual code. From these camp agreements, Colorado mining and water law evolved.

Arrogant altitude

These two core legal principles — beneficial use and “first in time, first in right” — came into play in the early 1930s on that August day when the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company executives stood on top of Independence Pass and figured they would blast a tunnel through and begin a legal water appropriation despite the geography.

According to a 1937 article, “The Independence Pass Transmountain Project: A Story of How Vision, Faith and Work Performed a Miracle for Crowley County, Colorado” — written by Frank Bancroft of the Denver Bar Association — the founders and stockholders of Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company (TLR&CC) were a group of “dirt farmers” who speculated that their irrigation supply was insufficient to their capabilities.

Having been beneficiaries of water from the Arkansas River in the Colorado Canal since the early 1890s, when the canal was trenched by mules, plows, men and grit, the farmers wanted to secure their lifeline of water. So they formed their company in 1913 and purchased both the canal and what is now Twin Lakes Reservoir on Lake Creek.

Water from the Arkansas flowing into the Colorado Canal produced cash crops and transformed the onetime buffalo-grass rangeland into irrigated farmland. But in the late 1920s and into the 1930s, drought and expanded production magnified their water shortage. That’s when they looked west for more.

Sugar City

Part of the original water-rights claim by TLR&CC, in the form of an adjudication petition filed in the Garfield County District Court in 1935, sheds more facts on the diversion of the upper Roaring Fork water. The petition asked the court to formally recognize the initial appropriation of the water, which had begun in 1930 when the boots-on-ground surveying for the project showed intent to divert the water and put it to beneficial use.

Coupled with an influx of inexperienced homesteaders, the growing demand for water about 48 miles southwest of Pueblo in Crowley County — deemed in the Garfield court document as “inadequately irrigated” — largely arose with the success of the company town of Sugar City, another 11 miles east and established by the National Sugar Company in 1891 to grow sugar beets. The town also became known for its cantaloupes, which were called “Sugar City Nuggets.”

The Nov. 24, 1922, Ordway New Era in Crowley ran an ad from the sugar company selling real estate and partnership that touted the company’s pitch as “The fifty-fifty factory town.” The company offered 80 acres of farmland at $150 per acre, 20% down and 10 yearly installments at 6% interest to “responsible and trained Colorado farmers.” This successful clarion call for more farmers would later sow the seeds for increased water needs in the 1930s.

In 1933 and 1934, the RFC approved loans of $1 million each ($40 million total today) to the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company, a nonprofit corporation of 550 Crowley County farmers, to build the Independence Pass tunnels. The company issued 56,000 shares of stock at $10 per share, the same number as the 56,000 acres they collectively farmed. The Colorado National Bank in Denver held the 30-year mortgage, which TLR&CC eventually paid in full.

‘Hole Thru’ party

With the RFC loan, the Independence Pass diversion project met the opportunity of demand, employment, presumption of supremacy over nature and Depression-era boldness, which history would ripen into unforeseen outcomes.

During that time of bootstrap development in Colorado, on Feb, 4, 1935 — a month with only 10 inches of snow, according to city records — dignitaries arrived on a special train from Denver and drove up to the West Portal camp at the entrance to Tunnel No. 1 at Grizzly Reservoir to witness Miss Virginia Waller of Chicago press the dynamite switch that “tumbled down the last wall of rock separating the east end of the tunnel from the west.”

The Feb. 7 edition of the Times reported: “There remains a good deal of trimming and lining before water can be sent through.” Although the 408-day excavation of Tunnel No. 1 slowed in tough sections, the Times reported that a world record was set on Jan. 29, 1935, “when the men pushed 85 feet in one day, 55 feet from the west and 30 feet from the east.”

On that day of Miss Waller’s finesse, the VIPs had eaten breakfast at the Hotel Jerome with Mayor F.D. Willoughby as the Aspen Concert Band played. After arriving at the West Portal with the band in tow for the celebratory explosion, the group boarded the ad hoc Lincoln Gulch mini-rail, called “The Dinkey,” and rode 9,600 feet into the tunnel (about halfway) to the “hole thru” ceremony.

“William Guthrie of Aspen, one of the ‘Dink skinners,’ was the motorman pulling the train of visitors, and the pilot car ahead was driven by Harold Rowland,” the Times reported. After the underground ceremony and inspection of the tunnel, the assembly enjoyed a banquet back at the West Portal as the band played on.

Not yet satiated, “the entire group returned to Aspen for a dance at Fraternal Hall, where upwards of 100 people, not counting employees and their wives” danced into the night, the day’s festivities all courtesy of Platt Rogers Inc. in an Aspen where straight-shooting businessmen prospered.

On the other side of the Continental Divide, the Crowley farmers postponed celebration until April, “once the tunnel is cemented and the water actually rushes down the ranges.” With a 10,500-foot elevation from the West Portal to the 10,450-foot East Portal — below and south of the bottom of the last switchback on the east side of Independence Pass — the water would roll just enough to obey physics.

Concurrently, the farmers submitted more plans to the RFC to build the second tunnel from Lost Man and the main stem of the Roaring Fork to Grizzly Reservoir, which would nearly double the volume to the main tunnel, according to the Sept. 5, 1935, edition of the Times. The 1935 Garfield court document said the total water-gathering area comprised 51 square miles of drainage at the crest of the divide.

White House involved

Gaining the water right for the Twin Lakes Project and getting federal funding were not without some opposition.

“The project was of interest to the legal profession, as many legal obstacles and hurdles were removed or jumped during the work,” said Bancroft in his account.

The issues raised included whether TLR&CC could complete the project and apply water to beneficial use in a reasonable time. During the water-rights process, some opponents also cited the 1922 Colorado Compact, according to Bancroft.

The compact is an agreement among seven U.S. states in the greater basin of the Colorado River in the southwest, designed at its inception to head off future controversies such as the ones on the table in the early 1930s.

And during the process to secure federal funding and approval for the project, Wyoming objected, but also to no avail. In the end, a deal was cut to give some Western Slope interests room to cut in line ahead of the new Twin Lakes priority date.

“For the first time the right to divert water from the Colorado River Basin to the eastern slope of the Continental Divide under the Colorado River Compact was made an issue between western slope users and eastern slope users,” Bancroft wrote in 1937. “The issue was settled by a recognition of the legal right to so divert under the compact and the practical side of the issue was adjusted by an agreement permitting western slope users to make filings for additional appropriations of water, and securing decrees therefore, ahead of the filings of the Twin Lakes Company.”

The June 2, 1933, edition of the Palisades Tribune of Palisade, Colorado, reported that even the White House became involved, when Congressman Edward Taylor of Colorado, a Roosevelt ally, objected to the diversion. So the White House leaned on the RFC to hold up the TLR&CC loan, but RFC’s lawyers countered that the ink was dry on the contract and the project must proceed.

Taylor agreed that the secretary of the interior could decide the issue as long as both sides of the divide could find agreement before the project started. Down the road, those political promises of westside consideration wouldn’t fully materialize.

Two-state solution

But the seeds of resentment of the less-populated Western Slope toward Denver-side growth had sprouted much earlier, as they watched funds from the state capital that had profited so well from Western Slope mining develop the Front Range while shortchanging the west.

In a florid letter published in the Times on Jan. 11, 1912, one of Aspen’s founding fathers Judge J.W. Deane, (namesake of Dean[e] Street at the base of Aspen Mountain) foretold that “Crafty inroad is being made upon water, which is our life, for the diversion to the plains far east of Denver by tunnels through the ranges, and far away electrical delivery of the power of our streams.”

Appointed by the Pitkin County commissioners to champion Western Slope interests at state conferences, Judge Deane rhapsodized for a “united Western Slope” to secede “as West Virginia did from Virginia in 1863” because — like Denver in 1912 — “her sustenance was being absorbed by unsympathetic, arrogant Richmond.”

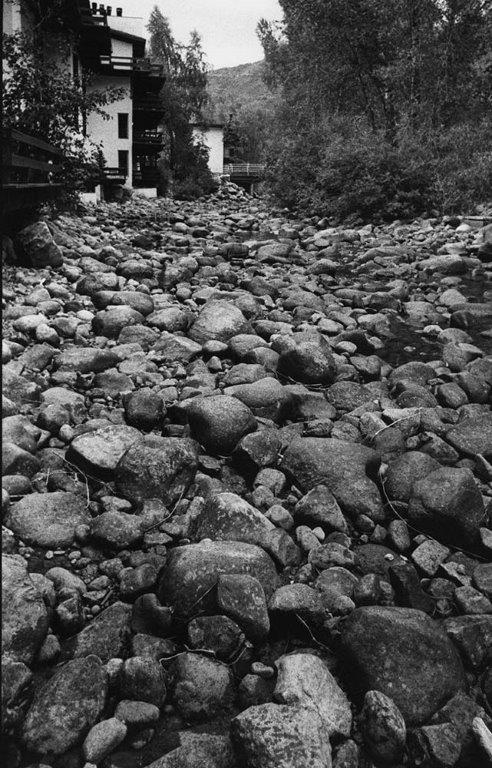

The Times on Aug. 24, 1937, reported that the water commissioner ordered TLR&C to decrease the flow of water through the tunnels so the Roaring Fork Valley would have ample irrigation supplies. Streams and creeks in the upper Roaring Fork basin had dried up during that summer, with the Colorado River at its lowest ebb since the drought year of 1934.

Looking at the dry creeks above town probably hit a nerve among Aspenites, who hadn’t expected that the allotted water going east would have such an impact.

Front slope, hind slope

In 1948, the Roaring Fork Valley was still objecting to diminished flow. The Sept. 9, 1948, edition of the Times reported that Colorado Congressman Robert Rockwell, chairman of the Irrigation and Reclamation Committee and who had a ranch in Paonia, met with the Aspen Lions Club and Judge William Shaw to hear complaints.

They inspected the Lost Man and Lincoln Creek sites, where they observed “the sad state of the Roaring Fork from the Lost Man dam on down to Aspen.” At the same time, TLR&CC was hoping to mitigate by lining some of the gathering canals on both ends of Tunnels No. 1 and No. 2 with “180 cars of cement” to lessen seepage.

Much to the indignation of the Western Slope, the flourishing east still held the view that western water was running unused across the Colorado border. The Sept. 30, 1948, edition of the Times railed against The Denver Post for promoting Front Range development “derived from a scheme to come with the diversion of water ‘simply going to waste’ on the west slope.”

The Times said that despite the dryness of Eastern Plains farms, the future of Western Slope agriculture, large coal deposits, electric power and the anticipated oil shale development of “Rifle into the oil can of the world” were being ignored.

Aspen grumbled how tunnel officials originally assured them that only “floodwaters” would be diverted. “One and only ONE look at the Roaring Fork now will prove that someone didn’t tell the truth,” the Sept. 9 Times declared. “The once roaring, boisterous stream is now a trickling seepage,” unable to irrigate the valley.

Visiting state officials proposed a reservoir just east of Aspen at the bottom of today’s North Star preserve to even the western flow. Nothing materialized during that era of bulldozer possibility, although today the Grizzly and Lost Man reservoirs can bypass water downstream to Aspen if eastside storage is full or repairs are occurring.

The long view

A 1976 account in the Aspen Historical Society’s archives by Bede Harris, born in Aspen in 1884, recollects the annual spring runoff before and after the transmountain diversion project.

Between 1893 and 1908, “the spring snowmelt was of such quantity, bridges were washed out.” Log abutments rotted. The Hunter Creek bridge — the major artery into town for hay, log haulers, dairy and livestock — disappeared overnight and took months to replace. At some point, the “hospital bridge” went downstream and a bridge that connected Spring Street to Oklahoma Flats washed out more than once.

The definitive 1896 W.C. Willits map of Aspen at the AHS shows eight bridges across the Roaring Fork — starting with the two railroad bridges that crossed between East Durant and East Waters avenues — down to Slaughter House bridge. The Midland and Rio Grande tracks looped back via Riverside Addition, east of Aspen, to the Smuggler mines.

Harris said abnormal runoff posed a problem nearly every decade, including one in the 1960s that flooded both the Arkansas and the Roaring Fork. “The eastern slope interests were not hesitant to open the valves at Lost Man and Lincoln, causing big problems below. The diversion seems to provide fairness only to those on the eastern slope.”

Lost habitat

Today in Pitkin County, below the three Independence Pass dams and through town, a skewed normal of the Roaring Fork has come to be accepted, a new reality wherein many don’t know better.

What is the minimal flow for the Roaring Fork that would sustain the natural conditions before the diversion, Harris wondered. His 40 years of post-diversion observations raised concern on a local scale. But it’s easy to extrapolate from thinking locally to thinking globally and to theorize whether large-scale plans to rearrange nature are ultimately wise.

Now, in contrast, the U.S. has about 75,000 dams and China over 80,000, most of which have altered downstream ecologies, diminished animal species and riparian zones, and at times demolished homes and towns during construction or upon failure. Studies cited recently on Rocky Mountain PBS say that so much trapped water in off-kilter weight pockets around the globe causes a wobble in Earth’s rotation and contribute to earthquakes, while we’re draining deep aquifers for mega-agriculture in deserts, causing fissures and sinkholes.

But in our backyard, Harris described the Roaring Fork below the dams, which could also characterize today’s new normal: “The rocks are high and dry in the stream bed … difficult to locate a water skipper, pollywog, toad or frog, smaller insects. … The water ouzel, pine marten, muskrat and beaver have been wiped out,” along with “sufficient willow, aspen, alder and shrubs.”

He noted how the river kept a balance when strong spring runoffs flushed out even the deepest holes all the way to the Colorado, cleaning out waste and providing clean sands for trout to spawn. He blamed the lack of annual scouring by strong native runoff for water-warming moss and algae in the river “near Gerbazdale,” below today’s Aspen Village trailer park, once known as the Gerbaz trailer park.

“In the long run Aspen and the Roaring Fork Valley has been the loser,” he wrote. This is true today in terms of impacted biology and less water.

Oh, the water

Whereas Bancroft’s document proclaimed that “faith and work performed a miracle for Crowley County,” that temporary Eden became an arc of history saddled with irony.

After a successful agricultural run between the 1890s and 1960s, Crowley farmers gradually succumbed to selling their water rights at a premium to Crowley Land and Development Company, which ultimately battled to a court victory in 1974, wherein it wedged water away from agriculture. The company then sold the rights to upstream Pueblo, Pueblo West, Colorado Springs and Aurora to fuel growth instead of food. The majority of TLR&CC shareholders became municipalities instead of farmers.

Today, the Crowley land is parched dust and tumbleweed, way worse than before the 1935 diversion first flowed and before onetime promises by long-gone CLADCO to restore native prairie vegetation failed. Of the “irrigated 50,000 acres, 2,500 remained” in 2012, Marianne Goodland reported in a story for the Colorado Independent in July 2015. And the few remaining farmers with water rights are not guaranteed water when there is not enough to go around.

As a result of the sales, Goodland wrote, the only bumper crops now are “noxious and obnoxious weeds. … Crowley is a parable for how bad things can get when cities and industry dry up farmland to buy rural water — a practice known as ‘buy and dry’ deals.”

On main street in Ordway, where TLR&CC still has its office in a small house, buildings and nearby old homes are vacant, many with asbestos from the golden era. Left high and dry, the county turned to prisons. One is state run, and the other is privately run.

Vital stats

Meanwhile, TLR&CC still completes its fiduciary duties to its water clients with a cool eye toward the Roaring Fork. No longer a group of earnest farmers, the company delivers 55% of its water shares to Colorado Springs, 23% to Pueblo, 12% to Pueblo West and 5% to Aurora, according to a July 27, 2011, story titled “Silencing the Roaring Fork River,” written by Brent Gardner-Smith and published in Aspen Journalism.

Gardner-Smith quotes Kevin Lusk, a senior water-resource engineer with Colorado Springs Utilities and the current president of the board of TLR&CC.

Regarding low western streams, Lusk said, “Instead of throwing more water at the channel, maybe you adjust the channel to the water that’s there. Kind of live with the reality you find yourself in. And that could certainly be a far better solution than just trying to return things back to the way they were. Even if you get the water back, it’s never going to be the way it was.”

Gardner-Smith cites statistics that indicate the way it might have been had the Roaring Fork been left to its native flow. TLR&CC “is allowed to divert up to 68,000 acre-feet in a single year and up to 570,000 acre-feet in a 10-year period.”

An average of 47,000 acre-feet diverted per year from the Roaring Fork River for eastern growth could be worth $1.6 billion a year on paper, when calculated from a 2014 value of $35,000 per share of TLR&CC, according to a 2014 article titled “High + Dry” and published in Denver’s 5280 Magazine. The story pegged the share value up 11,000% since 1960.

With flows of up to 625 cubic feet per second through the main tunnel to Twin Lakes, added to other diversion sources, the eastside reservoirs sometimes reach capacity. In big runoff years or during repairs, the Roaring Fork side has been caught by surprise by surges of water when TLR&CC reverses the spigot.

Like quarreling spouses on either side of the divide, this is akin to flushing the toilet while the other is in the shower. Still, questions remain in hindsight.

First, do diversions under the divide, including the Twin Lakes diversions, violate a premise of nature that balanced design to send water either to the Pacific or Atlantic oceans?

Second, should that natural prairie — once home to buffalo, countless other species and Native Americans — have been turned into an industrial farmland destined to be dried up by cities through “buy and dry?”

Despite efforts by environmental organizations to convince Colorado’s water community and citizens that rivers have a right to their own waters, Lusk’s observation that things are what they are is lodged in the Colorado constitution, which states that the right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses “shall never be denied.”

Ratified in 1876, the Colorado constitutional convention framed the constitution around anti-speculation, beneficial use and the rising agrarian reform movement that promoted small farmers over big money.

The concept of unused water is still a principle of Colorado water law, upheld by the Territorial Supreme Court in an 1872 decision based on the “imperative necessity” of water use for settlement in arid parts of the public domain, former Justice Gregory Hobbs outlined in his 2007 paper “The Public’s Water Resource.”

Now, as then, the push for more prosperity continues to look for additional water to feed the furnace of the economy, pitting sprawl against agriculture at the expense of nature. But in the 1930s, for better or for worse, government and business found a way to move mountains.

Tim Cooney is an Aspen-based freelance writer and former Aspen Mountain ski patroller. He writes about Aspen history for Aspen Journalism in collaboration with the Aspen Daily News. The Daily News published a version of this story on Saturday, May 23, 2020.