Editor’s note: This is the first in a three-part series on the events that led to the Northern Utes’ expulsion from western Colorado. Part one focuses on the events leading up to the historic Battle of Milk Creek against U.S. troops in a canyon 17 miles northeast of today’s Meeker. Part two, to be published on July 2, starts on the first day of the six-day Milk Creek stalemate, which provoked the incident at the White River Indian Agency where agent Nathan Meeker and his employees were killed. Part three, expected to run July 9, recounts the concluding aftermath, resulting in the “Colorow War.”

In 1879, multiple tensions simmered in the “Smoking Earth River” Ute Indian territory of the White River Valley in northwest Colorado, leading to the Battle of Milk Creek and the killing of federal Indian agent Nathan Meeker and other white men — an episode branded by the expansionists whites as the “Meeker massacre” in the ensuing rush to expel from nearly all of western Colorado the natives who had been inhabiting the land for centuries.

Caused by a violation of Ute territory by U.S. troops, a hellish battle of attrition in Milk Creek, 17 miles north of today’s Meeker sparked the rebellion at the nearby White River Indian Agency. That retribution had ripened from a chain of events of conflict, begun long before those fateful days when 24 Utes and 17 whites died at Milk Creek, along with 11 whites at the agency.

Had a series of lies and broken promises to the Utes — along with miscommunications and a dry summer — not formed a powder train, these hostilities might have been avoided.

The moral paradox of the massacre terminology, which branded Utes as having no right to resist white settlers and fevered prospectors who pressed the expansion of Manifest Destiny farther into ancestral native lands across the American West, stands as a historical misnomer because being somewhere first and then defending your life, family, home and property is a rudimentary precept of history.

Roland McCook, a historian and part of the Uncompahgre Band of the Northern Ute Tribe of today’s Uintah and Ouray Reservation, said in “The Utes and Meeker Incident,” one of his many YouTube Ute history teachings: “We call it the Meeker incident — referred to in books as a massacre. They [the Utes] were fully capable of killing everyone at both sites, but backed off. And so it can’t be a massacre.”

In stark contrast, well before the Meeker events, the Nov. 28, 1864, Sand Creek Massacre, near the Kansas border of Colorado’s Eastern Plains, exemplifies a profound massacre, where one side was unarmed. Given approval then by Colorado territory Gov. John Evans to eradicate a peaceful Indigenous camp, Col. John Chivington, an abolitionist and former Methodist pastor, led a 700-man artillery and cavalry slaughter of 150 Cheyenne and Arapahoe, most of them women, children and elderly. A mix of U.S. troops and frontier hooligan volunteers comprised his command, taking scalps and hanging private parts on their saddle horns as souvenirs to show in Denver.

Essentially, the American Indian Wars, or American Frontier Wars, a fight to claim more territory for European American settlers, began in colonial times and continued through the early 20th century. The last major conflict between the U.S. government and the Plains Indians occurred at the historic massacre of Wounded Knee in South Dakota, on Dec. 29, 1890, where 250 largely disarmed men, women and children of the Lakota were surrounded and killed. The gradual subjugation of the Colorado Utes — or Nuchu, meaning “mountain people” — between 1860 and the turn of the next century is another sad chapter.

Smaller boundaries drawn

While the Ute people were still abiding by the Ute Treaty of 1868 signed in Washington, D.C., by Ute Chief Ouray — which allotted much of western Colorado to them and ceded the central Rockies — prospectors, miners, and settlers began flooding into Denver and the mountains looking for gold and silver. The seven bands of Utes living in Colorado and Utah believed that the new treaty was to keep whites out, not the Utes in. Two earlier treaties, one in 1849 that surrendered Ute territory in northern New Mexico and another in 1863 that appropriated lands east of the Continental Divide, had already squeezed the Utes out of more of their territory.

The 107th meridian that runs north-south about 10 miles west of Aspen, near where Aspen Village is today, was the eastern boundary of the 1868 treaty — delineated north between the Yampa and White rivers, south by the New Mexico border and west by the Utah border — that further boxed in the ever-shrinking piece of Colorado territory left for the Utes, who once roamed all western parts of the state.

Before that, Ute oral tradition teaches that they have always lived across northern New Mexico, Colorado and eastern Utah, while modern anthropology dates their ancestral roots to 1000-1200 in the Great Basin, the vast area spanning from the Sierra Nevada to the Wasatch mountains. By 1300, the “Ute people” migrated to the Four Corners region. From there, they dispersed across Colorado’s Rocky Mountains over the next two centuries.

Though only lines on a map in the wilderness in 1868, prospectors and settlers intruded into the porous territory. After the 1879 Ute retreat from the area after the Meeker hostilities and the subsequent de facto dissolution of the treaty, settlers rushed in. By 1885, the Midland Railway followed those who had earlier disregarded the 1868 boundary of the territory given the Utes into Glenwood Springs, first called Fort Defiance in 1882.

After the 1879 events at Milk Creek and the White River Indian Agency, a decade of what the Denver newspapers popularized as the “Ute troubles” in northwest Colorado ensued. On June 15, 1880, to punish the northwest Utes, the U.S. government made Chief Ouray sign an agreement that dispossessed them of the White River reservation and removed them from Colorado. With the 1868 treaty then void, they were required to reside at the Uintah and Ouray Reservations in northwestern Utah.

But because the Utes were still permitted, per the 1880 agreement, to hunt their former northwest Colorado territory seasonally, roving Ute bands came into contact with settlers, causing the so-called Ute troubles. Adding to the mix, prospectors, miners, investors and fortune-seekers jammed up on the eastern side of the divide in Leadville, clamoring to usurp that once-reserved land as well.

Agricultural zealots

As this pent-up demand grew, the Jan. 30, 1878, edition of the Rocky Mountain News titled a news brief “Temperance — An Honest Man Appointed Indian Agent — Good for Father Nathan Meeker.”

Having failed to successfully perpetuate Union Colony — a communal utopian settlement he founded in 1869 at the site of present-day Greeley, Colorado — and deep in debt after starting the Greeley Tribune (named after his writing mentor Horace Greeley for whom he worked as an agricultural writer), Meeker took an 1878 offer from President Rutherford B. Hayes to become Indian agent at the far-flung White River Indian Agency deep in Northern Ute territory.

Appointed by presidents, Indian agents served as ambassadors to Native American nations while representing the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. They controlled trade between the U.S. and native communities and worked to acculturate natives into European American society.

Based upon temperance, religion, agriculture, education and family values, Meeker’s dream on the flat, semi-arid, wind-swept tract he had chosen for the Union Colony faltered under his enforced idealism, and he became embittered and stricter with his acolytes.

“He grew brusque and opinionated. He denounced traveling theatricals and dancing and picking wildflowers. He blackballed from membership in the Greeley Farmers’ Club all those who opposed his views,” Marshall Sprague wrote in “The Bloody End of Meeker’s Utopia,” published in the October 1957 issue of American Heritage. Disgruntled, the 500 members of the colony voted for other leaders.

Yet, with the lack of rain in the area, Meeker’s colonists constructed one of the first sophisticated Colorado water-diversion projects. Using a complex system of ditches that brought snowmelt from the mountains 70 miles away, their irrigation system proved to be a blueprint throughout arid parts of the state, Sprague wrote.

With a desire to retry his reformist values on the Utes, and to pay off his colony’s financing debt to the late Horace Greeley’s heirs, Meeker gratefully, if not naively, took the $1,500-a-year job ($45,000 today) as the Northern Utes’ new Indian agent. With his Calvinist work ethic and a dalliance with opium — according to the online Colorado Encyclopedia — he was hellbent on converting the free-roaming Utes into sedentary Christian farmers.

Sparked by new zeal, the stooped and worn 61-year-old Meeker moved to the agency in the spring of 1878 with his wife, Arvilla — nee Arvilla Delight Smith, daughter of a sea captain — along with their daughter, Josephine, and a group of employees. In agreement with the economic expansionists and hordes of homesteaders pushing the boundaries of the Western frontier, Meeker believed that the Indians were a roving obstacle to those who deemed productive agriculture and ownership as the only righteous uses of the land.

Even before Manifest Destiny pushed into the American West, “Christian Discovery” — based upon 15th century papal bull, royal grants and colonialism — justified white European seizure of foreign lands.

In 1823, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, who famously established separation of powers and judicial review, affirmed the Christian Discovery concept in his “Indian Trilogy” decisions as the basis of land title in the United States, Peter d’Errico wrote in his University of Massachusetts essay from 2000, “John Marshall: Indian Lover?” Essentially, Marshall formed the concept of “tribal quasi-sovereignty,” subordinating Indian occupancy under U.S. primacy and Federal Indian law, which “secured the chain of land title derived from royal grants and colonial [Christian] discovery,” d’Errico wrote.

But before the “Maricat’z,” as the Utes called the white man, the Utes led a life where they owned little — except a lot of horses — and belonged to the land, while Meeker aggrandized that he could solve the entire Western Indian problem by preaching property allotments to the natives.

Sprague wrote in American Heritage that Meeker explained how he “would teach the Utes modern farming and irrigation so they could all be rich, live in houses, ride in carriages, use privies, sleep in beds, wear underwear and send their children to the agency school.”

To this end, Meeker moved the original agency eight miles west to the fertile, well-manured Powell Park, where the Utes grazed about 2,000 ponies. The resultant battle of Milk Creek and the killings at Meeker’s agency, triggered by his request for military backup when things didn’t go as he planned, are detailed in a 2022 account by J.B. Sullivan: “The Incident at White River, The Battle of Milk Creek,” a footnoted manuscript at the Rio Blanco County Historical Society in Meeker.

Historically, there were many Ute bands made up of family groups. Over time, there were seven distinct bands, each with its own hierarchy of chiefs, until in 1868, the U.S. government appointed Chief Ouray of the Uncompahgre band chief of all Utes. Before the white settlers, they lived a life of low impact on the land. Although migratory with seasonal weather, thereby allowing the land a chance to restore itself, the Utes’ favored pursuit when not hunting for food was horse racing on a track. Meeker planned to demonstrate the better life by plowing up their track and fertile grazing land to plant crops.

With the help of his assistants and sporadic Ute cooperation, Meeker built streets, dug irrigation ditches, erected fences, constructed new buildings and plowed 80 acres, he claimed. This development plan included Maricat’z-style houses for chiefs and wood stoves for the surrounding tepees.

Meeker’s official job was to act as government liaison and distribute annuity goods to the Utes in payment for reduced access to their ancestral land and hunting grounds. Employing a divide and conquer strategy, he managed to persuade some Utes to try settling down, while most resisted and camped nearby. His strategy backfired, and Ute distrust of Meeker grew when he suspended promised government supplies if they didn’t obey. Meeker expected the Utes to farm instead of hunt. When they didn’t, he stalled the food allotments they had been promised, claiming the goods were stuck in transit, causing them to hunt more, which Meeker resented as time stolen from agriculture. The result: Many Utes who were counting on food allotments were caught short of sustenance with the onset of winter.

Then tensions came to head when a Ute fired a warning shot near a white plowman to scare him. Fearful of escalation, and without telling the Utes, Meeker sent a mounted messenger to Rawlins, Wyo., who telegraphed to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 10, 1879, Meeker’s request for military protection of his family and employees.

Through their own scouts, the Utes got word of the U.S. cavalry mobilizing to the north at Fort Steele near Rawlins. When the contingent of troops started marching toward them, the Utes, many of whom were aware of what happened at Sand Creek 15 years earlier, assumed the worst — and they prepared. At the same time, the choleric Indian agent ceased his fevered plowing and withdrew to his residence with his family, withholding from the Utes that his many letters of alarm to the governor and the Bureau of Indian Affairs had asked for troop protection.

In Robert Emmitt’s 1954 book, “The Last War Trail,” which provides a vivid history of the Utes leading to the Meeker hostilities, Emmitt highlights Meeker’s correspondence, including the Sept. 10 telegram. “I have been assaulted by Chief Johnson [Canavish] … . Plowing stops; life of self, family, and employees not safe; want protection immediately,” Meeker’s telegram to the BIA read.

Adding to the tension, the battle-jaded U.S. cavalry and infantry — then on the march — were eager for action. Ultimately, Meeker’s arrogance and stubborn expectations of Ute compliance in his official position would turn out to be the death of him, on the fateful day of Sept. 29, 1879.

Northern Ute chiefs

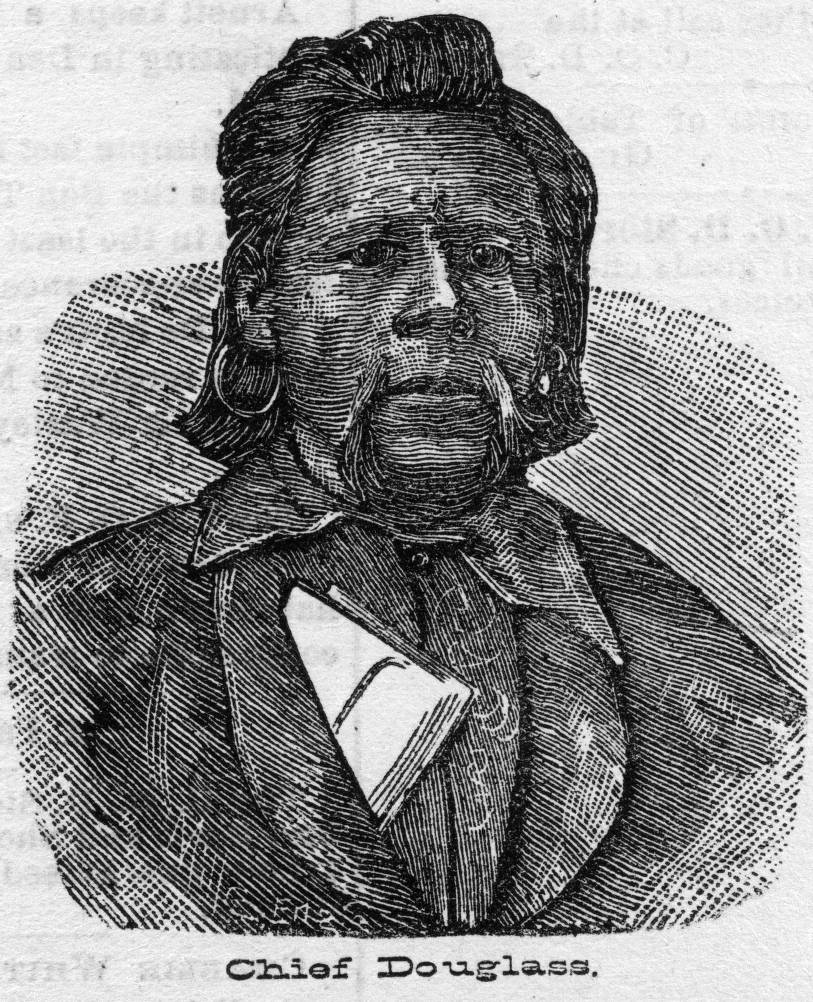

The main Ute chiefs in the White River district — Quinkent (“Douglass”), Nicaagat (“Jack”), Canavish (“Johnson”), given easier names by the whites, and Colorow — understood the inevitable white tide. At first, they appeased Meeker to keep the fragile peace while he insisted the Utes call him Father Meeker. Some dabbled in his farming lifestyle, leaving untended crops for long hunting trips, infuriating Meeker. But homogenization into white-culture knockoffs became an indwelling indignation.

The elder chief, Quinkent, lived in a house at the agency Meeker built for him, while medicine-man chief Canavish lived there in a tepee. Perhaps Quinkent had seen too much change, making him more willing at first to adapt. Colorow, with about 200 followers, and Nicaagat’s band were harder to convince and camped south of the agency.

An Apache orphan, Nicaagat had been sold by the Spanish as a slave to a Mormon family who educated and whipped him, until he ran away and the Utes adopted him. He somewhat shelved his resistance, because Ouray, head chief of all Utes north and south and headquartered at the Los Pinos agency near today’s Montrose, had directed him to make peace with the white man. As a skilled negotiator of four treaties, Nicaagat had memorized them all, and with a stunning profile fit for a coin, he sometimes hid his intelligence by speaking pidgin English — an abbreviated, simplified speech.

Originally a Comanche, Chief Colorow gained his name — meaning red, because his skin tone contrasted with the darker Utes — from the Ute band that captured and raised him after the tribes battled in New Mexico. Later, he married three Ute sisters from the White River area and had 13 children. Known for his playful spirit and friendship with the whites, his love of their biscuits, and his arm-wrestling and horse-racing skills, Colorow’s view of the settlers changed to distrust and animosity after his son Tabernash was questionably shot in August 1878 by a member of a sheriff’s posse in Middle Park, near today’s Granby, Colo.

While Quinkent was head chief at Meeker’s agency, Colorow and Nicaagat maintained the old ways. But as buffalo and other game became scarce because white hunters were feeding mushrooming mining camps, their Ute bands became more dependent on promised government allotments, which Meeker doled out for good behavior.

Yet, the Utes still hunted north of the reservation, as the 1868 treaty allowed, searching farther and coming into conflict with white settlers in the North Park area above today’s Hayden, who blamed them for any crimes, skirmishes or fires in the particularly dry summer of 1879. All of this willfully fanned the statewide refrain that the Utes must go.

In August 1879, Nicaagat traveled to Denver to talk to Gov. Fredrick Pitkin (of today’s eponymous Pitkin County). He told Pitkin that agent Meeker was no good: “Somebody tells lies and the lies go to the papers. The Utes want peace. We do not dig in the ground and spoil the grass. My people hunt and get food,” Emmitt quoted Nicaagat as saying in “The Last War Trail.” Pitkin, who was notorious for espousing Indian removal, told Nicaagat that all people have to work, and the Utes, with nearly one-third of the state, could be rich if they worked the land for minerals and farmed.

Meanwhile, Meeker had angry outbursts as he obsessed over the Utes’ need for so many horses, which competed for water and plowable acreage. In an open letter to Pitkin dated Sept. 10, 1879, published with a race-baiting newspaper article in the Sept. 16 edition of the Rocky Mountain News and headlined “Untamed Utes,” Meeker complained about too many horses grazing.

Sullivan’s White River manuscript attributed 100 horses to Quinkent, 300 to Nicaagat and his son, and 300 to Canavish and his son. These ponies counted as wealth, but they competed with Meeker’s 300 cows. One of the earliest tribes to utilize horses from the Spaniards in the 1600s, the Utes called them “magic dogs” and spiritually connected to the stamina, power and mobility of their mounts, which enabled them to migrate and hunt buffalo.

In the fall of 1878, according to Sullivan, as a way to justify his horses, Canavish fooled Meeker into giving his racing horses extra feed, saying he would make them into plow and wagon horses. The chief then cleaned up in the spring of 1879 among his peers who bet against his better-fed horses. Later, realizing he had been fooled, Meeker threatened to withhold all Canavish’s allotments — a tactic he often used on Utes who were disinclined to farm — and then plowed all around Canavish’s house. Angered, Canavish pulled Meeker from his house and pushed him over a hitching post, which Meeker recounted as being “assaulted in my own house … and considerably injured,” in the letter to the Rocky Mountain News.

Meeker’s Sept. 10, 1879, request for protection to the BIA was forwarded to the War Department and then to Army Gen. William T. Sherman, who approved three companies of cavalry with mounted infantry be sent from Fort Steele to the White River unrest. In anticipation of the approaching troops, perceived as the enforcing arm of their eradication, the Utes prepared to defend themselves if the 1868 treaty boundary at Milk Creek was crossed.

Meeker had set himself up by writing hyperbole to the newspapers; by lying to the Utes about the availability of their allotments; by saying he hadn’t requested troops when, in fact, he had; and by claiming that the government endorsed killing excess horses to make room for crops and cows.

Maj. Thomas T. Thornburgh marches

On Sept. 21, 1879, Maj. Thomas Tipton Thornburgh left his command post of Fort Steele, near Rawlins, with 190 soldiers, a surgeon, officers, scouts, more than 300 horses and mules and 25 wagons manned by teamsters with supplies for 30 days. Their job was to carry threat to the doorstep of the Ute reservation and reinforce Meeker, if needed. All options were open to Thornburgh, who devised a plan to camp on the reservation border and assess the situation once there.

Thornburgh, a Civil War veteran and post-combat West Point graduate who fought in the Sioux Wars, left his wife and several children at Fort Steele to lead the mission. Called a soldier’s soldier and a disciplined leader by his men, he had suffered the death of his young son, George Washington Thornburgh, six months earlier.

The troops averaged 25 miles per day on the 170-mile journey to the Milk Creek reservation border, arriving 17 miles northeast of today’s Meeker on the morning of Sept. 29, 1879. Ute women had earlier named the creek after retrieving milk cans there from an overturned freighter. The creek funneled into a canyon — not ideal terrain for a large military detachment to approach potentially hostile forces.

At the mouth of the canyon, a sizable meadow on the north side of the creek would serve as the base camp for the supply wagons. However, the troopers quickly discovered that because of the dry summer of 1879, Milk Creek was not flowing. Instead, stagnant pools compromised their water needs for so many men and stock.

Nicaagat tries for peace

Earlier, after learning that Meeker had requested troops, and with the circumspection of a man who had negotiated with the Maricat’z before, Nicaagat tried to talk to Meeker. But the agency leader refused to confer, hiding in his house and afraid that his confrontation with Quinkent would escalate.

Next, Nicaagat and a few Ute men rode to find Thornburgh on his way to Milk Creek, a few days before their arrival. The chief first stopped and bought 10,000 rounds of ammo at Peck’s store in Hayden, just in case, which he sent back with two men to the Ute camp, according to Sullivan’s manuscript. From there, Nicaagat found Thornburgh’s nearby camp. He and Thornburgh already knew and trusted each other, from Nicaagat’s earlier work as a scout. They agreed that Thornburgh and five men would come alone to assess Meeker’s actual situation at the agency, to avoid battle and affirm whether Thornburgh needed to advance.

In preparation — if troops crossed Milk Creek onto the reservation — Colorow and Canavish had already mobilized about 50 well-armed warriors to hide along the ridges where the trail narrowed through the canyon toward the agency grounds, while Quinkent remained at the agency with some braves, as Ute women and children evacuated farther south from the agency. An account in the Oct. 15, 1879, edition of the Rocky Mountain News said there was a much greater number of Utes assembled on the ridges.

But about midday of their arrival on Sept. 29, because of the lack of pasture and water in the dry Milk Creek at his command camp, Thornburgh decided, on the advice of a scouting party, to move his camp south to Little Beaver Creek, just inside the reservation. From there, he planned to travel unarmed with five men to the agency, as agreed to with Nicaagat.

By some accounts, word of Nicaagat’s arranged powwow between Thornburgh and Meeker hadn’t reached Colorow’s incited young braves along the ridges. As Nicaagat approached to meet Thornburgh’s liaison group, he spotted troops moving to the better water source and wondered if Thornburgh had gone back on his word. He then rode to Colorow’s ridge group and urged them not to fire on the troops who had crossed the Milk Creek boundary, so he might yet confer with Thornburgh. At the same time, Lt. Samuel A. Cherry and a detail had gone around the canyon ridges for a defensive check, where he discovered Colorow’s many Utes ready to defend the reservation boundary.

A change of tide

Cherry quickly reported the Ute position to Thornburgh, who ordered the main body of troops behind his small negotiating detail to reverse and set up a defensive wagon corral back on the north meadow by Milk Creek. Cherry waved his hat and yelled to the Utes on the ridge to confer, while Thornburgh rode slowly back to the wagon corral trying not to provoke fire. With adrenaline on edge, a first shot rang out, and Pvts. Michael Firestone and Amos Miller were killed by Ute fire. Capt. J. Scott Payne’s horse was shot out from under him.

A party of Utes then circled behind Cherry’s troopers and Thornburgh, where they skirmished, as the main body of troops formed the wagon corral. Multiple accounts vary, but according to Mark Miller’s book “Hollow Victory,” a Ute sharpshooter shot Thornburgh in the head and he fell from his saddle 500 yards from the defensive corral. His body lay there for days before retrieval under fire from the wagon corral.

The troopers had circled the wagons with the tongue and yokes facing in. They arranged supplies, erected tents to block vision while digging trenches and piled a circular breastwork of trench dirt to prepare for a long siege. Much fire was exchanged and both sides sustained deaths. A sharpshooter, who was said to be Canavish with a Sharps buffalo rifle, picked off most of the troopers’ horses and mules during the six-day battle — described in many accounts to be the longest of the American Indian Wars, dated by some as lasting from 1609 to 1924.

Early in the battle, the Utes set fire to the brush above the wagons. But before flames reached them, troopers had burned a clear line around their 75-yard-by-25-yard corral. An intermittent rain-and-snow mixture created a stew of mud, blood, waste, brimstone and putrefaction, along with the thrashing chaos of dying animals. After killshots, the animal carcasses were stacked in the defensive breastwork along with the bodies of soldiers wrapped in canvas, from where troopers fired back.

Seesawing between harrowing attritional engagement and long, gnawing pauses, any movement or exposure would be a target for Ute sharpshooters. Stealth nighttime trips to retrieve stagnant water from Milk Creek about 300 yards away exposed the troopers to ambushes. To pass time during pauses, the soldiers staged debates between the 17 trenches: They discussed “economics, politics and government,” complete with trench judges, Sullivan recounts.

At a certain point, the battle settled into entrenchment between a static defensive position and a surrounding offensive advantage. Either the Utes would slowly pick off the dug-in soldiers and then storm the barricades, leading to many more deaths on both sides, or cavalry reinforcements would arrive and turn the tables.

Two critical events

However, two critical events occurred that changed the future narrative on the first day of battle. First, Ute scouts rode to the agency to warn Quinkent that the soldiers had committed an act of war by crossing the Milk Creek boundary, reaffirming their belief that the troops, all along, aimed to march south to the agency. With that, Ute warriors from the Milk Creek fight opened another front at the agency, killing Meeker and his employees. Second, U.S. Deputy Marshal Joe Rankin, a scout and guide, set out just after midnight on Sept. 30 from the battle toward Rawlins to telegraph for reinforcements for the surrounded White River expedition. He was one of three sent, so one might succeed.

Riding his wounded horse, as recounted in Miller’s “Hollow Victory,” Rankin pushed the first 20 miles before his horse collapsed. Known as a fighter and expert horseman who liked to wear fancy buckskins, his historic ride of 140 miles in about 25 hours for reinforcements involved three fresh mounts, appropriated at settlements along the way. On his fourth, for the last 28 miles to the Rawlins telegraph office, he straddled an unbroken horse, which bucked for the first few miles. Rankin arrived at the office near midnight the next night, where he telegraphed for reinforcements.

One of the other two rescue riders encountered Capt. Francis Dodge on patrol with three dozen Buffalo Soldiers — originally formed as separate units of black soldiers during the Civil War — north of Hayden. Dodge then wheeled south on a 70-mile march to Milk Creek to reinforce the besieged troopers there. They arrived the next day, Oct. 1, the Colorado Encyclopedia recounts, riding through gunfire, lifting morale and reinforcing the entrenched troops for another five days.

Telegraphed word reached Col. Wesley Merritt at Fort David A. Russell, in Cheyenne, Wyo., who requested backup troops from other garrisons by train to Rawlins. He then began his march to turn the tide with the 500 men he had, arriving at Milk Creek on Oct. 5, Emmitt writes in “The Last War Trail.” Within days, Merritt’s backup totaled 1,100. Overwhelming numbers — coupled with orders from Ouray at the Los Pinos agency to Colorow and Nicaagat to cease resistance — eventually caused the Utes to withdraw.

That conclusion is simplified in retellings. However, the Rocky Mountain News on Oct. 15, 1879, tells a different account from a courier dispatched by Merritt to Fort Steele to request Mountain Howitzer cannons, as he “attempted to dislodge the Utes from the commanding bluffs.” His building troop strength motivated the Utes to withdraw to another higher-ground position south, closer to the agency.

With that withdrawal and because of the “fearful stench” of the dead animals at the corral, Merritt moved his troops south on Milk Creek out of range of the Utes’ new position. For three more days, Merritt dispatched cavalry to engage the fortified Ute location. Officers reported back that the Utes numbered in the hundreds and had plenty of ammunition. Merritt surmised that Ute reinforcements were arriving from the Uintah reservation in Utah and from the Southern Utes, while most accounts say Ouray held back the Southern Utes.

Thornburgh’s troops fell under command of wounded Capt. J. S. Payne for the duration of the siege. Numbers differ, but most accounts tally 17 whites killed and 44 wounded, along with 24 Utes killed and unknown numbers wounded, while 127 horses and 183 mules of Thornburgh’s detachment died.

Awaiting further orders, Merritt then maintained his large encampment, prompting the Utes to disband and blend into encampments west and south. That second-phase standoff further delayed Merritt from reaching the Indian agency and discovering the scene of the killings there until 12 days after they took place.

***

Part two in this three-part series will continue on the July 2. As the battle of Milk Creek began midday on Sept. 29, 1879, between encircled wagons of U.S. troops and Ute Indians firing on them from the surrounding ridges, a shocking confrontation unfolded at the White River Indian Agency 17 miles south, near today’s Meeker.

This story ran in Aspen Daily News.