And He Shall Lead Them

Lester Cotton is 6-4 and 328 pounds, which is good because he will be carrying the hopes and dreams of thousands with him next fall when he plays for Nick Saban.

JACKSON, ALA. -- The two little boys slip through the fence to the field and head straight for Lester Cotton. Lester's school, Central High in Tuscaloosa, is warming up for its game against Jackson High in the first round of the 5A high school playoffs. But the boys can't wait. Their families have been hearing about him for months. They have to meet him. Lester is 6-foot-4, 328 pounds of offensive lineman, and the boys barely come up to his waist. Their eyes widen as he kneels between them so their mamas can take a picture. But they still want something more. Lester has to get to the locker room. Come back after the game, he says. I'll take care of you.

By the way: The boys are wearing jerseys for the other team. Lester is used to this by now. A couple of weeks before, at Helena, one of the opposing team's managers did a giddy hop after he met Lester in the handshake line. Football fans across the state follow his progress the way day traders check the ticker. This has been going on from the moment Lester committed to play for Nick Saban at Alabama this fall. In this state, that makes him royalty.

The statewide news site AL.com named Lester the top football prospect in Alabama before the season started. ESPN's rankings list him as the seventh-best guard prospect in the country (Lester plays left tackle for Central but is expected to move to guard in college). He has a suitcase in his closet full of letters from all the schools that want him. Most have given up because the Crimson Tide have a literal home-field advantage; you can see Bryant-Denny Stadium from the Central High campus. Some recruits play college ball thousands of miles from their high school. Lester is going five blocks.

This fits Lester's nature. Not long ago, he asked his mother whether she'd still cook for him when he comes back to the house. The training table at Alabama is spectacular, but it's not the same as his mama's mac and cheese.

"Why would you want me to be just what I am now? I've got to change. That's the only way to make it."

- Lester Cotton

It's hard for any child to go off to college. You have to get grown in a hurry, and most are not ready. Lester totes two extra burdens. One is the expectation from Alabama fans that he will be a star for the Tide on Saturdays. The other is the hope of his teammates, teachers and friends that he will shine a light for Central High. The second burden might be heavier than the first.

In the '80s and early '90s, Central High was the best Alabama could offer -- fully integrated, with strong academics and a powerhouse football team. It was a unified school for the whole city. But in 2003, after a court decision lifting a federal desegregation order, the city broke up Central and added two new high schools. All three schools have a majority of black students, but Central's district draws from Tuscaloosa's west side, the poorest part of town. Students in nicer neighborhoods near Central were zoned away to Northridge High, up on the other side of the Black Warrior River. Central is now 98 percent black, with nearly two-thirds of its students on the free-lunch program. Last year the state of Alabama named it a "failing school" because it has finished near the bottom of the state's schools academically for three out of the past six years.

Central's football team has suffered, too. The Falcons won a state title in 2007, but coming into this year they'd had just three winning seasons since Central split. A lot of Central's students -- and a lot of the adults who work with them -- feel like the city has left them behind. To them, Lester is a flare sent out into the world beyond.

"One thing about our students," says Clarence Sutton Jr., Central High's principal. "They have to see someone who looks like them, who came from their background, be successful for them to believe they can be successful. That's why Lester is important. Your story can impact others if you write a good story with your life."

The story Lester is writing is about change. He liked being just one of the boys, but his coach needed him to be a leader. He would be fine with a normal life, but his school needs him to be extraordinary. At his core he's a homebody, but football pushed him into a bigger life.

On national signing day Wednesday, barring a shocking change of heart, Lester will make things official with Alabama. A few of his teammates will resent the attention he'll get. He'll lose some old friends. It's a short trip from Central High to the University of Alabama, but it crosses a border between worlds. A lot of Lester's old life can't come with him.

Lester doesn't talk a whole lot, but he has thought about all this. He is 18, right on the pivot between boy and man. Walking toward one means walking away from the other.

"People say, 'Don't change,'" he says. "Why would you want me to be just what I am now? I've got to change. That's the only way to make it."

Lester Cotton, a high school senior at Central High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, hopes to fulfill his lifelong dream by playing football for the University of Alabama.

THE PRINCIPAL LOVES to tell the story. He got a call to come meet a new student who was transferring in and wanted to play football. He got to the office and found Lester and his younger brother. He figured the brother was the football player. He thought the giant in the black, horn-rimmed glasses was the dad.

This was the spring semester of Lester's freshman year. His mom, Cher Cotton, had just moved the family from East St. Louis, Illinois. Lester was actually born in Tuscaloosa, but Cher moved to East St. Louis when Lester was 8 to be closer to the Illinois side of her family. Their neighborhood was rough. After a police officer got killed behind their apartment, Cher didn't let her kids outside for a whole year except for school and practice. They watched Alabama games on TV. Lester looked over at his mom one of those fall Saturdays and said: I'm gonna play there.

There was not much reason to believe him. He always had the size -- he was 9 pounds, 13 ounces at birth, and every year he grew taller and wider than the other boys. But Lester liked video games more than playing outside. Football was Cher Cotton's idea. She signed him up for a pee wee league to keep him active and off the streets. He liked playing. He didn't much like practicing or working out. Cher Cotton says some of the people Lester hung out with in Illinois told him he wouldn't amount to anything. Lester turned inward and absorbed it. She had thought for years about going back home. One day she pulled her kids out of school, packed their stuff and headed for Alabama.

That's how Lester ended up at Central High, and that's how he met Dennis Conner.

Conner played linebacker at Central in the early '80s, at its height as the unified city school. He played college ball at Jackson State, then came back to Central as an assistant. In 2010, he took the job as head football coach. His job goes deeper than building a team. Many of the players don't have a father around. Lester does -- his dad, Marvin Jackson, owns a construction business in town. But Conner fathers Lester, too. The day they met, he looked at Lester and said: I want to make you somebody.

Conner and his staff worked Lester in the weight room and taught him blocking techniques. They helped him focus -- he always had a short attention span -- and built his confidence. The summer before Lester's junior year, some players showed up one Tuesday morning for offseason weight training. Conner came by and took Lester up the street to Nick Saban's football camp on the Alabama campus. Lester had no idea he was going. Conner had already paid the fee.

Conner went back to the Central weight room, figuring Lester was about to learn how much harder he still needed to work. Then coaches Conner knew at Saban's camp started texting him. Lester was whipping everybody in the drills.

That afternoon, Lester called his coach:

I think you want to come back up here.

Why?

Coach Saban wants to meet you.

Then Lester went home and found his mom:

Mom, you need to come back to the camp with me.

Why?

Because we're going to have a meeting with Coach Saban.

Boy, stop playing.

They all met that evening. Saban said he wanted to look at some more film but thought that, if Lester kept up his grades, Alabama would offer him a scholarship. Word got out about the camp, and other schools jumped in to recruit him. Alabama made its offer, and so did lots of others. The suitcase in the closet filled up with letters. Lester tore the meniscus in his knee and missed half his junior season. Alabama's offer held. In February 2014, at junior day -- when a group of junior prospects visit the campus together -- Lester committed to the Tide.

That's when people he had never met started coming up to him at the grocery store.

Lester always had the size to play football, just not the drive. His mom enrolled him to keep him active and off the street. Marcus Smith

LESTER IN FULL football gear is a sight. His face mask is a dense grid. The straps on his shoulder-pad belt stick out from his chest. Because of that, his No. 76 jersey tends to ride up, leaving an undershirt to cover his gut. All year, he wore the red-and-blue camouflage cleats he got in an all-star camp. In the NFL, he'd be a walking uniform violation.

The one thing missing is his glasses. Lester is farsighted. He hates contacts, so he wears glasses to see up close. He has worn the same style of thick, black frames since kindergarten. This makes him look like the world's largest hipster. The glasses don't fit under his helmet, so he hands them to a manager before he takes the field. Without glasses, parts of the game are a blur. Lord knows what he would do out there if he could see.

Most teams keep track of pancake blocks, in which an offensive lineman simply knocks a defender to the ground. It's a stat that tends to get some home cooking, depending on who's doing the count. Central High's tally says that Lester had more than 200 pancake blocks this season -- about 20 a game. That's absurdly high for any player. But watching Lester up close, the count feels a little light.

Conner was never that worried about the physical part of Lester's game. Lester always had the size and quick feet. Most games, he'd be the best player on the field. Conner wanted him to be the best in the locker room, too. He sat Lester down before his senior year. You're the one everyone here is looking at, Conner said. I need you to lead.

It's the fifth game of the year, and Central is playing at home against its crosstown rival, Paul W. Bryant High, named for the Bear himself. On Central's second possession, a Bryant defensive end tries to beat Lester around the corner. Lester pushes him sideways a good 10 yards, and Central quarterback Tyler Bell runs through the hole for a touchdown.

Central keeps running left, behind Lester, and the Falcons keep scoring. But Bryant scores even faster. In the third quarter, there's a scrum over a fumble, and when the players un-pile, Lester doesn't get up. He took a hit that broke his knee brace. The stadium goes mute. But after a couple of minutes, he gets up and walks off. A few plays later, he's back in the game.

The fourth quarter turns into a movie. Central, down 37-34, stops Bryant on fourth down as the Central band plays Teddy Pendergrass' "Close the Door." But Central fumbles and Bryant recovers with four minutes left. Then Bryant fumbles it at midfield with 1:30 left. Central drives inside the Bryant 20, and the clock dips under 30 seconds, and finally Bell finds Timmie Gibson over the middle for the winning touchdown.

The whole team huddles at midfield after the clock runs out, hugging and hollering, and Lester is loudest of all: "That's how we stay a family! That's how we stay a family! That's a family!"

The huddle breaks, and Lester staggers over to the track that surrounds the field. He goes down on all fours. The trainers bring him wet towels and ice. He pulls himself up and sits down on their golf cart. Conner circles back toward him and leans in close, bracing his hands on Lester's knees.

"How you feel now, that's how I feel. Exhausted but happy," Conner says. "That's the way to lead your team. That's the way to lead your team."

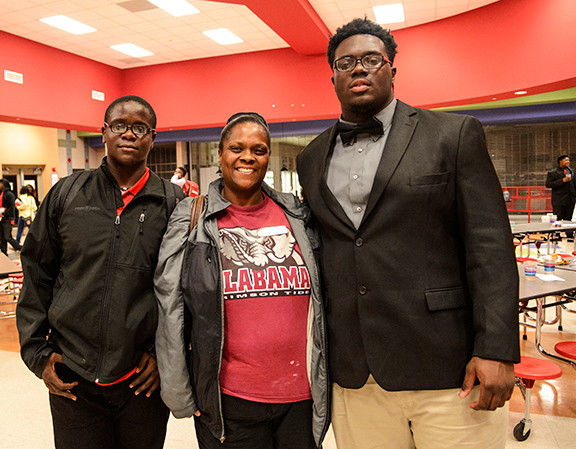

Once he starts at Alabama, Lester won't be far away from his mom, Cher, and his brother, Martavious Ward. AL.COM/Landov

LESTER SHARES a bedroom with his brother, Martavious Ward, a freshman defensive lineman for Central. A crooked Alabama poster hangs on the wall, and a photo sheet of Lester with Conner is pinned on top of that. Lester's size 15 shoes are piled up at the foot of the bed. "He's a typical teenager," Cher Cotton says. "I have to get on him about cleaning his room."

Lester's mom has a steady job -- she's a cook at Bryant Hall, the university's athletic complex. (She started working there well before Lester became a prospect.) Lester and his family don't have much to spare, but they're better off than most families on the west side. So many kids at Central live in homes where every week is a scramble for a paycheck on Friday and to put food on the table. College, much less a scholarship to college, is a bitter dream. Sutton, the principal, says Central has a few really tough kids, some in gangs. They leave Lester alone. He has what they crave: a ticket out.

A few months ago, Lester took some of his teammates over to the university. He showed them around the weight room, took them to the practice fields, let them walk the grounds where the top program in all of college football does its work. Not long after that, Conner heard one of the players grumbling to Lester: You ain't going nowhere but Bama.

"You're the one everyone here is looking at. I need you to lead."

- Dennis Conner

"Nowhere but Bama?" Conner says, his voice jumping an octave. "Nowhere but Bama? Do you know how many people are lined up to get into Bama? A couple of the kids are jealous because Lester is getting something they ain't got. Lester has a good heart. He wants all the boys to like him. He wants to be one of the boys. But you can't lead that way. You can't really lead anyone that knows your secrets."

Lester has spent his three years at Central transforming from an oversized teenager into a football star. A lot of lessons come with that change, and they're not just football lessons. They're for anybody who wants to lead, or just to get good at something. They're lessons for people who want to grow. Or need to grow up.

Lester hopes the NFL is in his future, but he has backup plans. He watched Conner carefully and thinks he'd like a job like that. He also took classes in masonry and learned how to lay brick. He dreams of building his mother a house with his own hands, using his own money.

I want to make you somebody, Conner told Lester on the day they met. Lester believed him.

Lester describes his senior season this way: "My expectation was, like I said, to be a leader. But it was knowing that I got family as a football team and knowing that these are my brothers and I backed them up like they backed me up in anything. In any way possible."

Cher Cotton describes her son a different way: "How can I say it? You know how that flower blooms? It's all bunched up at first and then it lets go? He has done bloomed to the whole flower."

Lester's past circled back to him just a few weeks ago. In late December, during practice for the Under Armour All-America Game in Florida, coaches rotated linemen to face off in one-on-one drills. Lester ended up across from Terry Beckner Jr. They grew up together back in Illinois, played ball, became good friends. Now Beckner is a 6-4, 298-pound defensive tackle -- the No. 2 overall prospect in the whole country, according to ESPN's rankings.

Lester lined up against the guy he knew from East St. Louis, when Lester wasn't so sure of what he could be.

The coach blew the whistle. The two linemen crashed together.

Lester threw Beckner to the ground.

text

Lester is farsighted but hates contacts. He hands his black-framed glasses to a manager before going on the field. Marcus Smith for ESPN

THE FIRST-ROUND PLAYOFF game goes sideways for Central. Jackson is powerful and swift -- the Aggies will end up making the state semifinals. Central can't keep up. Late in the fourth quarter, it's 35-7 and both teams are running out the clock. But then Central fumbles and a linebacker from Jackson picks up the ball near midfield. He has nothing but clear grass ahead. Lester, blocking on the other side of the play, turns to see the Jackson player sprinting away.

Lester outweighs the Jackson player by roughly 160 pounds and has to cut all the way across the field. It looks like impossible geometry. But Lester hits full speed, and all of a sudden he is a tanker truck set loose on the grass. He outruns the angle and takes down the Jackson player at the 13. The Jackson crowd's cheers melt into disbelief, as if they just saw magic.

Lester sprawls on the turf, spent. Two teammates haul him up and help him off the field. It is the last play of his high school career. He drops down on a worn-out wooden bench. He leaves his helmet on. Behind that big face mask, no one can see him cry.

Most of his teammates cry, too. They cry as the clock drains to zero, and they cry on the walk to the locker room, and they cry as they strip off their jerseys and pads. It smells like dirty socks and sounds like a Baptist funeral. The Falcons have finished the season 6-5. It's not a great record, but they have won more than they lost, and at Central High these days, that matters.

Conner stands in the middle of the room and tells his players he loves them. Then he goes to the seniors, one by one.

"Enjoyed it," he says to Lester. "Great season. Great season."

These are this team's final moments together in football gear. Once the players strip it off, they move into a different world. A few might get to play ball at a small college, maybe a two-year school. Most will never play another game. They dawdle awhile before starting to pack. Lester has one more job. The two little boys are standing at the edge of the field, waiting for him.

It turns out one of the boys is a brother of the Jackson player Lester chased down at the end. Lester tries to smile. He's ragged, exhausted, caked in sweat and tears. The boys' cheeks glow in the cold. They just want a little something more. A souvenir of the night Lester Cotton came to town.

He gives each boy one of his lineman's gloves. They put them on and run off laughing, little Michael Jacksons dancing in the end zone. By the time they look back, Lester has already turned around. He limps toward the locker room to change. In a few minutes, he'll be on the bus to Tuscaloosa.

ESPN feature producer Scott Harves contributed to this story.

Tommy Tomlinson is a contributing writer for ESPN. You can reach him at tomlinsonwrites@gmail.com.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "And He Shall Lead Them."