(Above) New York in the 1920s—Arthur Barry’s burgling heyday.

(Above) New York in the 1920s—Arthur Barry’s burgling heyday.

Sometimes it seems as if I spent my entire boyhood watching

It Takes a Thief. Although my parents deemed me far too young to see that 1968-1970 ABC-TV series when it aired originally, I caught up with the show years later in weekend reruns. It starred Robert Wagner (previously cast in movies such as

The Pink Panther and

Harper) as Alexander Mundy, an oh-so-suave cat burglar, pickpocket, and master of disguise, who—in exchange for his release from prison—went to work for America’s fictional SIA (Secret Intelligence Agency), employing his criminal talents for espionage purposes instead. The program was inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1955 romantic thriller,

To Catch a Thief, but was also a part of the late-1960s TV spy craze (which had earlier given birth to such classic dramas as

The Avengers,

The Man From U.N.C.L.E.,

I Spy, and

Mission: Impossible).

It Takes a Thief was broadcast for only three seasons, yet it left behind 66 hour-long episodes—all of which I watched over and over and over again, much to the dismay of my mother, who believed I should be out playing or doing homework rather than relishing Wagner’s efforts to deceive espionage agents and seduce lovely (and sometimes dangerous) young women. But in a sense I

was doing homework, consuming the show in search of expertise, for I had convinced myself that I wanted to be Alexander Mundy when I grew up.

While that never happened,

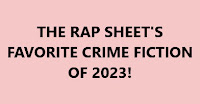

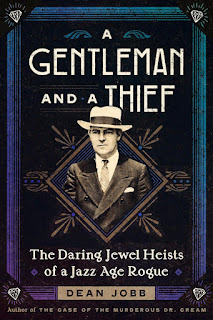

It Takes a Thief did leave me with a lifelong interest in stories about accomplished—and, especially, sophisticated—larcenists. Which explains why I was hungry to read Dean Jobb’s

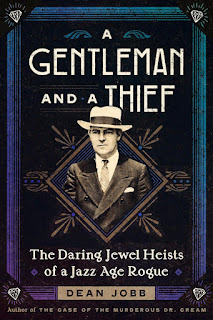

A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue, released recently by Algonquin Books.

You will likely remember that Jobb (pronounced like

robe, rather than

robb) penned

one of my favorite non-fiction books of 2021,

The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer, about remorseless Canadian poisoner

Thomas Neill Cream; and before that, he drew widespread acclaim for his 2015 work,

Empire of Deception: The Incredible Story of a Master Swindler Who Seduced a City and Captivated the Nation, which examined the career of

Leo Koretz, a Ponzi-schemer of the 1920s who, according to

The New York Times, was “the most resourceful confidence man in the United States.” Now, in

A Gentleman and a Thief, he looks back at Arthur

Barry—an American jewel thief known for his debonair mien, audacious escapades, and deep-pocketed victims—who, for more than half a dozen years, stole an estimated half-million dollars in precious stones

annually. Not bad for a former juvenile delinquent whose own mother thought him destined for either the gutter or the hoosegow.

Arthur Barry was born to working-class Irish parents in the industrial town of Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1896. His path to a lifetime of criminality was not perfectly straight, but seemed nonetheless fated. He became a safecracker’s errand boy in puberty, and at 15 committed his first home break-in. “He always said he was big for his age,” Jobb recalled in

a recent interview with CrimeReads. “After he started hanging out with an older crowd of guys who did things to make five bucks here and there, he became a courier for a fellow who was making explosives for safecrackers. Barry would take, by train, suitcases stuffed with cotton and a bottle of homemade nitroglycerin. In a great story Barry related, he said the fellow told him,

Don’t shake it. And don’t move it too much. And try not to drop it.”

His mother wasn’t wrong about Barry being a likely candidate for incarceration: his first jailing came in 1914, after he was wrongly convicted of a burglary in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Barry was remanded to a reformatory, but subsequently enlisted with the U.S. Army, and in 1918 was sent overseas during World War I. In France, he performed heroic service as a medic, was wounded in the leg and gassed, and then returned to America in 1919, taking up residence in New York City. However, with a criminal record and no trade skills, honest employment was hard to find. “The men in the first waves of soldiers sent home from France claimed most of the jobs,” Jobb writes, “as well as all of the glory.” Barry weighed his options, and determined that his best path to prosperity was on the wrong side of the law. “The thought of violence repelled me,” Barry later contended, but he reasoned that stealing expensive gems was “clean-cut and sportsmanlike,” and “as close to a victimless crime as he could imagine.” He was once quoted as saying, “People rich enough to own jewels never had to worry about their next meal.” And insurance payments could assuage the pain of their losses.

Between 1920 and 1927, Arthur Barry proved himself to be a crackerjack “second-story man,” using ladders to break into the bed chambers of the rich and famous—sometimes while the estate owners were entertaining friends downstairs—and purloining their precious possessions. He found many of his “marks” (he preferred to call them “clients”) via newspaper society pages, and lacked not at all for boldness in his capers. Clad in a tuxedo and exercising a glib tongue, he’d crash parties thrown at the estates of upper-crust residents on Long Island and in Westchester County, New York, as well as in Connecticut, in order to case them for future nighttime invasion. Among his targets were a Rockefeller, an Oklahoma oil tycoon, a member of the British royal family, a famous polo player, and a legendary Wall Street investor. At the height of his nefarious career, Barry stole an estimated half-million dollars in precious stones annually. His biggest score was in Manhattan in 1925, when he broke into the six-room Plaza Hotel suite of Jessie Donahue, heiress to the

Woolworth five-and-dime store fortune, and filched “almost $700,000 in pearls and gems—the equivalent of $10 million today,” according to Jobb.

Before police knew Barry’s identity, the public marveled at his felonious exploits, dubbing him a “Prince of Thieves” and an “Aristocrat of Crime.” Newspapers commented on his courage and athleticism; after one mansion robbery in 1925,

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle opined that anyone capable of scaling the building’s façade so easily “would make some of the stunt artists of the movies envious.” On occasions when he was confronted by his victims, he exhibited a polite

and calming comportment. Once, he relinquished a pair of pricey pinky rings he was assured held sentimental value to the owners, leading one of those “clients” to tell reporters, “I know he’s terrible, but isn’t he charming?”

(Left) Dean Jobb (photo by Kerry Oliver).

“These were serious crimes,” the author reminded CrimeReads. “He violated people’s privacy. He shattered their sense of security. But he didn’t hurt anyone. And he did perfect this soothing approach, which really makes him a different kind of criminal. It certainly made him a more enjoyable character to bring to the page. He didn’t have a cruel streak or anything.”

Barry was also something of a romantic. In 1924, he was introduced to Anna Blake, the wife of a New York City taxi entrepreneur and a Democratic Party organizer, who was then in her mid-30s (several years older than Barry). In short order, Anna’s husband died and she became increasingly friendly with Barry, eventually marrying him, apparently unaware of his criminal endeavors or the fact that some of the jewelry he gave to her was “hot.” Not until the law finally caught up with Arthur Barry in 1927 did Anna realize the cause of his frequent absences (to pull off heists) and that his money didn’t come from gambling windfalls. Yet she didn’t abandon him, nor did he leave her open to prosecution as an accomplice in his crimes. Rather, he confessed to dozens of burglaries to protect her.

Like Jobb’s studies of Thomas Neill Cream and Leo Koretz,

A Gentleman and a Thief is the sort of popular history that might enthrall even readers who generally shy away from non-fiction historical accounts. Told with brio, historical details galore, dramatic chapter openings, and attributes familiar from top-drawer crime fiction, it’s a love story, to boot. It is, in the end, a gem of tale.

So delighted was I with this account, that right after turning its last page, I contacted Jobb’s publisher and arranged for an e-mail interview with the author. I wound up asking him about his background in journalism and teaching; the public’s enduring interest in true crime yarns; how he selects the subjects of his books; the next historical crime figure he intends to tackle; and much more.

J. Kingston Pierce: How long now have you been a journalism professor at the

University of King’s College, in Halifax, Nova Scotia?

Dean Jobb: I started teaching research, investigative reporting, and media law courses part-time in the School of Journalism in the 1990s. I became a professor and full-time member of the journalism faculty in 2004 and joined the faculty of the university’s Master of Fine Arts in Creative Non-fiction program in 2016. I teach writing-craft courses and oversee a cohort of students during their two years in the program, as they work on a non-fiction manuscript.

JKP: Before you embarked on writing books, you were a reporter. When and how did you join that estimable profession, and how long did you work as a reporter? How did it lead you into academia?

DJ: I joined the Halifax

Daily News in 1983 and moved to the city’s

Chronicle Herald in 1984, where I covered crime and the courts, pursued investigative projects, and served as an editor. My part-time teaching at King’s led to the full-time appointment in 2004, when I left the

Herald. I continue to write for newspapers and magazines.

JKP: You’ve been writing books about historical crimes for more than three decades,

beginning with

Shades of Justice in 1988. What was it that first drew you to this colorful, if sometimes gruesome subject matter?

DJ: I graduated from university with a history degree and when I got my first job as a reporter, I was assigned to the legal beat. Since I was immersed in covering crimes and trials and I was interested in history, I began researching and writing feature stories that re-created intriguing and forgotten crimes of the past—murders, swindles, bank robberies, whatever. The quirkier and lesser-known the case, the better.

JKP: There seems to have been a significant uptick in public interest in true crime subjects over the last decade or so. What do you think is responsible for that development?

DJ: True crime has always been popular. While the number of books, podcasts, and documentaries has exploded in recent years, you only have to dig into a century-old newspaper to see how much our ancestors also craved their true crime hit. Crimes were reported with lurid headlines and in remarkable detail, with whole pages often devoted to verbatim transcripts of trial testimony. “If there is one thing more than another of which the average man likes to read the details,” the

Chicago Daily Tribune noted in 1880, “that thing is a first-class murder with the goriest of trimmings.” Today’s intense interest in true crime would come as no surprise to a time-traveler from the past.

JKP: We’re all familiar with George Santayana’s aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But what are the specific benefits of knowing the history of human criminality?

DJ: Crimes can help us understand what the past was really like. A murder or other heinous crime catches people—crooks and many witnesses alike—on their worst behavior, stripping away the veneer of respectability and good-old-days nostalgia and shining a light on how people behaved and what they were capable of. And many crimes are a product of their time and place, exposing the role wealth, class, privilege, and prejudice played not only in the commission of the crime, but in how the police and the courts dealt with offenders and whether justice was done.

JKP: You started out by writing books about “mischief, mayhem, and murder” in Nova Scotia. What convinced you to finally tackle historical crime of potentially greater interest to a larger audience?

DJ: Many of my early true crime stories ranged beyond Nova Scotia’s borders—mutinies on the high seas, offenders who fled to other parts of Canada or to the United States, newcomers who killed or robbed banks, and even some Confederate pirates and raiders who took refuge in the province during the Civil War. The first major international crime story I uncovered was the arrest of fugitive Chicago con man

Leo Koretz at a Halifax hotel in 1924.

JKP: So how did you first come across “slick, smooth-talking, charismatic lawyer” Koretz, whose story you tell so brilliantly in

The Empire of Deception? And did you right away see it as a gold mine?

DJ: I was at the Nova Scotia Provincial Archives [in Halifax], flipping through a card index under the heading “Crimes and Criminals,” when I spotted an entry with a brief description of Koretz’s arrest. It listed a few newspaper accounts describing how he had duped investors—who believed he controlled vast oilfields in Panama—promised and paid enormous returns, and swindled them out of millions of dollars. It was a Ponzi scheme and Koretz had mastered it for almost two decades before Boston’s

Charles Ponzi came along and gave the scam its name.

Koretz was the

Bernie Madoff of the 1920s. I knew instantly it was a great story and fabulous fodder for a book.

JKP: After deciding to plumb Koretz’s short but eventful life, how long did it take you to accumulate all the material you felt you needed in order to write the book?

DJ: It took a lot of detective work, both here in Nova Scotia and in Chicago (as well as in New York City, where Koretz lived on the lam before fleeing to Canada). I picked away at the research for many years, in between work commitments and researching other books. The story had never been fully told and piecing it together—and finding every news report, document, court record, and scrap of information I could—became as much an obsession as a challenge.

JKP: How often do you think you have found the perfect historical crime subject for a book, only to later realize it does not boast enough intrigue or complexity? Can you give an example?

DJ: I have researched several true crime projects that looked promising but lacked the scope, surviving records, or compelling story and characters needed for a book. One that stands out is the beauty queen who killed her wealthy and abusive husband, a theater impresario, in their villa on the French Riviera. Her trial was an international press sensation during the Depression, her ordeal was the basis for a Hollywood movie, and my research unearthed the material needed to tell the story. But the case seemed to lack the impact and drama needed for a good book. I’ll likely rework it into a feature article at some point.

JKP: On top of teaching and producing books, you’ve been writing a column about historical crime for

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine since 2018. Do some of the subjects you reject for book-length treatment show up in that column, “

Stranger Than Fiction,” or do you go searching for different sorts of stories to address there?

DJ: These are true crime stories that catch my eye as I’m reading and doing research. As the column’s title suggests, I’m looking for quirky, untold stories as well as the real-life crimes that inspired writers of crime fiction.

JKP: The poisonings by Dr. Thomas Neill Cream seem ideally suited for book-length scrutiny. When did you first learn of his crimes?

DJ: I had heard of Dr. Cream and spotted news reports about his case now and then while researching other crimes of the Victorian Era. He’s still listed as a possible suspect in the Jack the Ripper murders—despite the fact he was behind bars in an Illinois prison in 1888, when the infamous Whitechapel killings occurred in London—and as I recall, one of those lists caught my eye.

JKP: Cream’s tale is incredible, partly because he was able to get away with his misdeeds for so long, thanks to the fact that police departments—especially those operating on opposite sides of the Atlantic—didn’t communicate well during the late 19th century. But it also benefits from his having been an early example of a serial killer, who “murdered simply

for the sake of murder,” rather than having a motive rooted in emotion or profit. How important was it to you that you explore the historical context of his career, in addition to his individual slayings and eventual downfall?

DJ: Dr. Cream’s weapon of choice was strychnine and he convinced most of his victims to take medicine he concocted that contained a lethal dose of the deadly poison. As I took a closer look at his crimes, I realized there was more to the story than how he murdered at least nine women and one man in three countries. The real questions to be asked were, how did he get away with his crimes for so long, and how was he finally caught in 1892? That’s a bigger story that illuminates the misogyny and class divisions of the times and exposes how wealth, privilege, primitive forensics, and crude policing methods allowed him to kill with impunity.

JKP: As you observe, reports about the Ripper frequently loop in Cream, if only because his last utterance, as he awaited the grip of the hangman’s noose in 1892, was allegedly, “I am Jack the ...” Is there any validity to stories of that abbreviated dying confession?

DJ: There’s no evidence Cream ever said those words. The claim was made in a brief article published in a British newspaper in 1902—a decade after Cream was hanged—but it was widely republished and a legend was born. I hope my book, and my research showing the origins of this myth, may finally put to rest the notion he was “Cream the Ripper” as well as a serial poisoner.

JKP: I appreciated your care with historical context again while reading

A Gentleman and a Thief. On top of Arthur Barry’s feats as a confidence trickster and proficient pilferer of expensive gemstones, you acquaint us with the criminal environment of 1920s New York, the staggering differences between that period’s haves and have-nots, prison conditions of the time, and the histories of some of Barry’s acquaintances and victims, from Harry Houdini and the Prince of Wales to Jessie Donahue, Lord Mountbatten, and Percy Rockefeller. It seems you do as much research into the milieu surrounding your criminal protagonists as you do into the protagonists themselves. That must surely add many hours to your task of producing a book. Is such research as satisfying to you as it is to your readers?

DJ: Writing can be hard work but research is fun, so it’s hard to stop looking and to start writing. Research is detective work, treasure hunts, and mystery-solving rolled into one. I’m re-creating a lost world and inviting readers to travel back in time, and that means weaving in vivid details of what life was like in Barry’s glitzy, Jazz Age, live-for-the-moment world without detracting from the action and his story. My goal is to bring the past to life for readers.

JKP: How do you recognize that moment when it’s finally time stop all your researching, and start writing?

DJ: Ideas for scenes and chapters emerge as I’m doing my research. When a part of the story seems to be coming together, I begin to write it and focus my research on filling in the information needed to produce a draft of that part of the book. I revise and add details to these drafts as my research continues and I find new information.

JKP: You observe that in addition to being audacious, Arthur Barry was a successful “second-story man” because he planned his break-ins carefully. That doesn’t seem like rocket science, though. Wouldn’t planning have been useful to all such thieves? Why did Barry know to concentrate on planning more than his light-fingered rivals?

DJ: Some of his precautions were obvious, such as wearing gloves to prevent leaving fingerprints. But donning a tux to crash parties at posh estates? Posing as a repairman so he could enter a mansion and disable the burglar alarm? Pretending to be a police officer and calling in a phony accident so he could trace the license plate of a limousine carrying a socialite wearing expensive jewelry? Reading a jewelers’ trade magazine to teach himself which gems he should steal and how much they were likely to be worth? Barry was as imaginative as he was meticulous, and seemed determined to master his chosen profession, jewel stealing. There’s a reason he got away with his crimes—and jewelry worth $60 million today—for seven years.

JKP: Like Cary Grant’s character in the 1955 film

To Catch a Thief, Arthur Barry was gallant and debonair for a cat burglar. He also had a romantic side. Well into his career in crime, Barry fell in love with a widow named Anna Blake, who would become his prime source of support and, later, his fellow fugitive. How important was their romance to your development of Barry’s story?

,%20Nov%201,%201932.jpg) (Above) This November 1, 1932, illustration from The Daily Notes in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, shows Blake with husband Barry.

DJ:

(Above) This November 1, 1932, illustration from The Daily Notes in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, shows Blake with husband Barry.

DJ: Anna Blake plays a vital part in this story. When Barry was caught in 1927, he confessed to ensure she was not charged as his accomplice (she insisted she had no idea he was a burglar, and my research confirmed this). Blake stood by him and when she became seriously ill [from cancer] in 1929, Barry staged a spectacular prison break to be with her. They lived as fugitives for three years. A key to telling her story was my discovery of a series of newspaper features published in 1933 in which she revealed details of their strange and dangerous life together. This became a love story within a true crime story.

JKP: Were you at all intimidated, when preparing your own Arthur Barry book, by the fact that Neil Hickey had published a well-known work on that same subject,

The Gentleman Was a Thief, back in 1961? Was there much information you found that Hickey did not have?

DJ: Hickey’s book was incredibly useful—Barry cooperated with him and revealed a lot about his life and crimes. It was a great starting point for my research, but I unearthed reams of new material and discovered there was much more to the story. Barry only recounted a few of his major burglaries in his interviews with Hickey and I was able to tie him to dozens of others. And at times Barry tried to rewrite his past. He claimed to have planned and executed almost all of his burglaries by himself, for instance, even though he worked with an accomplice—James Monahan, a childhood friend—for years.

JKP: You teach creative non-fiction. What are the elements of

A Gentleman and a Thief that would demonstrate clearly to your students how to organize and tell history to a general audience?

DJ: The

creative part of creative non-fiction is the way the story is told, using the tools of fiction writers—vivid scenes, compelling characters, dialogue drawn from the historical record—to tell a true story with the drama and narrative drive of a novel. It’s not, however, an invitation to fictionalize or to embellish. You can’t make up stuff. That’s why deep research is so vital. You can’t imagine and you can assume, so you have to find the details and quotations and descriptions needed to tell a gripping, page-turning story.

JKP: Finally, what forgotten crime story are you working on next?

DJ: I’m already working on a new book for my publishers, Algonquin Books and HarperCollins Canada—a real-life whodunit with the working title

Murder in the Cards.

Joseph Elwell, one of the world’s foremost authorities on the game of bridge, was shot to death in his Manhattan home in 1920. Elwell’s books on bridge and his skills as a gambler at the card table, the racetrack, and on Wall Street made him rich. His murder was front-page news for months as New York’s crime reporters and top detectives scrambled to crack the case. There were plenty of theories, possible motives, and suspects, including prominent New York businessmen and socialites, former lovers—along with their jilted boyfriends and husbands—underworld figures, and racetrack rivals. No one was ever arrested, however, and the murder remains unsolved.

The New York Times called it “the perfect mystery.” I’ll re-create the crime and the police and press investigations, assess the clues, and answer a century-old question: who killed Joe Elwell?

,%20Nov%201,%201932.jpg)